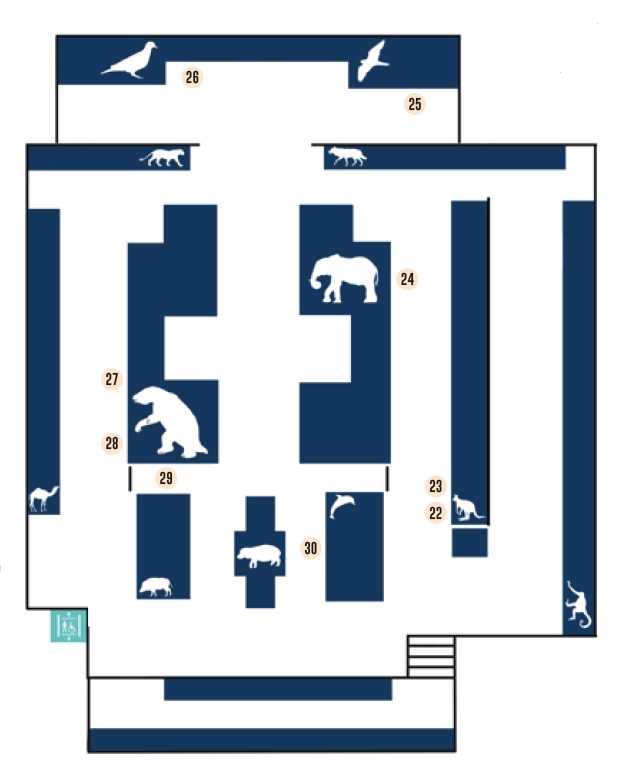

In April 2025, a group of 30 Year 12 students from schools and colleges across the UK attended a residential programme run jointly between the Museum of Zoology, Clare College and Kettle’s Yard to create a temporary exhibition exploring art and nature. Fragile Harmony was the result. The title and all the text you can see on this blog post was written by the students. They chose the theme of the exhibition, its contents, and worked with graphic designers from Paper Rhino to create its feel and identity. The exhibition is on until the end of 2025, so do come and see this fantastic work in situ.

We would like to thank the Isaac Newton Trust’s Widening Participation and Induction Fund to supporting this project, Paper Rhino for their work turning their ideas for the logo and visual identity of the exhibition into fantastic graphic designs, and the Botanic Garden, Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, and the Women’s Art Collection at Murray Edward’s College for welcoming us into their collections for inspiration and ideas.

Now over to the students, the Cambridge Future Museum Voices:

Fragile Harmony

This is an exhibition that asks the question: how does art and storytelling shape our perspectives on nature? We are young people from across Britain brought together by our curiosity about creative expression and our biological environment.

We designed this exhibition following a week of reflection on various artefacts and specimens in the collections of Kettle’s Yard and the Museum of Zoology. It asks you to consider the depth of each individual specimen and art piece as a pair, and the messages they hold. By connecting with individual objects in this way, we uncover the fragile harmony formed when they come together.

We are eager for you to explore the complex relationship between the natural world and the man-made, and to pause to appreciate the beauty in nature and art. We hope that this exhibition will allow you to open your eyes and see past the labels we impose on the natural world and answer the question: How can we embrace art and nature to help us find balance?

Upper Gallery

1. Great Auk and ‘Bird Swallowing a Fish’, Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, 1914

written by Isabella

Look at the great auk. Now look at Gaudier-Brzeska’s ‘Bird Swallowing a Fish’. One bird is full of life, the other is merely bones. Humans drove great auks to extinction, collecting them like art as their population depleted. A hunter described killing an auk how “the bird made no sound as I strangled it”, highlighting human’s lack of respect for nature’s fragility.

The auk’s story juxtaposes Gaudier-Brzeska’s sculpture, the use of art enables him to convey the liveliness of the bird whilst the auk skeleton stands solemnly. The only time we would ever see an auk’s liveliness is in art.

2. Butterflies and ‘Stag’, Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, 1913

written by Diya

Look at the stag and the butterfly side by side. At first they may seem as though they have nothing in common however, they both have defence mechanisms, with mimicry seen in the butterfly species and the antlers on the stag. These organisms would not be associated with one and other due to the fragility of the butterfly and the more aggressive nature of the stag, but this shows all animals have defence mechanisms, including humans. It is as though the artist tries to make the stag appear more delicate through the use of continuous lines and this shows how there are two sides every creature.

3. Jewel Beetle and ‘Dancer’, Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, 1913

written by Lili

The Jewel Beetle and Henri Gaudier-Brzeska’s ‘Dancer’ both reflect the challenges of femininity in a patriarchal society. Male beetles, drawn to shiny, beautiful cues, relentlessly pursue females—often to their own death. Similarly, the ‘Dancer’, bare and exposed, depicts the vulnerability women face under constant male gaze. Just as beetles are prized for their beauty, women are often treated as delicate, graceful prey under the male gaze. Both beetle and sculpture serve as symbols of exploitation masked as admiration, subtly echoing the danger of being seen but unheard, desired yet voiceless.

Jewel Beetles or “Buprestidae” are considered the “most beautiful” beetle species, and males will often be attracted by visual cues such as bright, shiny colours. Additionally, male beetles are known for their persistence during mating where they will often only withdraw by consumption via predator or death from dehydration.

This is an unfortunate reflection of women’s struggles, living in a patriarchy. Much like the name ‘Dancer’ suggests, women are often painted as graceful and fragile, and are exploited for their beauty and perceived ‘femininity’.

The statue presents the ‘Dancer’ in her bare beauty, and this dwells on the vulnerability of being female, whether human or insect, as it is near impossible to avoid the male gaze, especially those of ill intent.

Whilst the moral compass of males in both scenarios differ immensely, both beetle and statue are a stark reminder of how the female body is too often regarded as an item or given right, and that the statue will forever keep dancing for its potentially undesired audience.

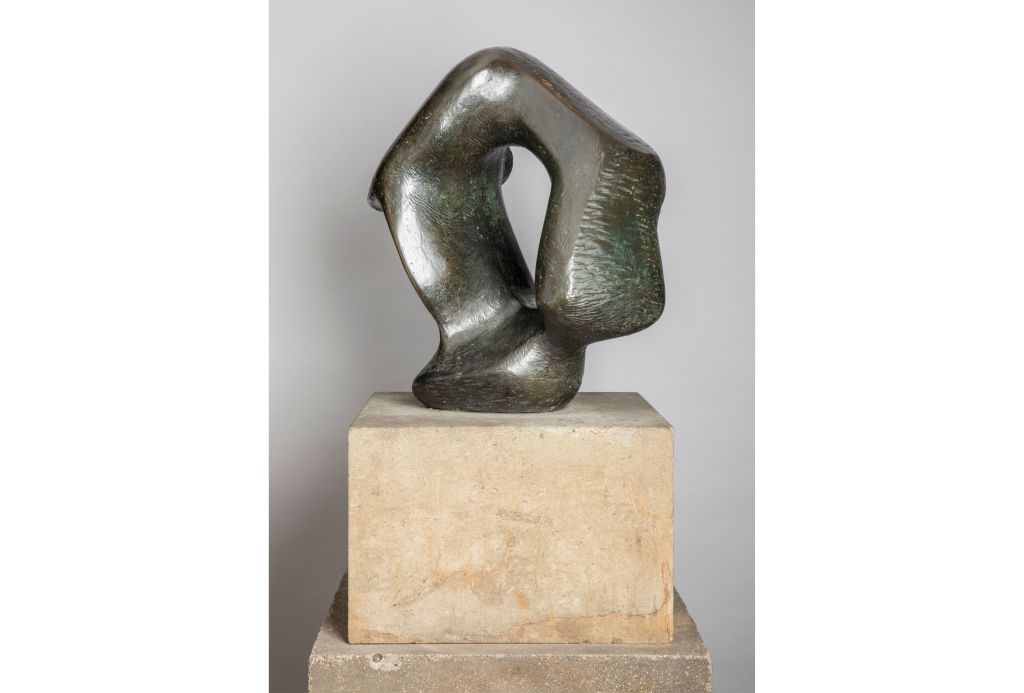

4. Insects, ecosystems, and ‘Sculptural Object’, Henry Moore, 1960

written by Zoe

Almost half of the 2.15 million described species on Earth are insects. Mammals and birds make up less than 1 percent. Despite their immense importance in maintaining our ecosystem, from managing waste to produce food, insects have very little floor space in exhibitions like this.

The sculpture by Henry Moore epitomises the female struggle, a pelvis bone designed to withstand immense pressure, just like the female spirit.

Both subjects, despite their importance in their respective ecosystems, have been historically overlooked and uncelebrated. Balance can be restored if we celebrate the uncelebrated. How

can you show appreciation for the uncelebrated?

5. Hairy-nosed Otters and Khymer Buddha

written by Amber

Examining the preserved hairy-nosed otters conveys how intertwined nature and human choice are in presenting museum objects. The otters appear in a naturalistic scene, however the complicated process behind preserving spirit specimens requires human intervention. From the sculpture of the Khmer Buddha, I drew meaning from its relationship with the delicate flower. The statue was faded and human-made while the flower was vibrant and organic. The complicated connection between man and nature is explored within both of these objects. The buddha and its flower represents the contrast while the otters convey the human aspect behind presenting natural specimens.

I chose to compare this spirit specimen of two otters and a Khmer Buddha statue from Kettle’s Yard. I believe that these objects both explore the complex relationship between man-made objects and choices and natural specimens.

Initially, I was drawn towards these pieces because they exuded a feeling of inner peace; the otters appeared rather content (almost as if they were sleeping) while the Buddha sculpture (and its flower) seemed to represent a higher meditative state of tranquillity. Upon deeper reflection and analysis, both objects revealed themselves to present a profound connection between the natural world and the human-made.

From the stone sculpture (by an unknown artist) of the Khmer Buddha, I drew meaning from its dichotomous relationship with the delicate flower placed upon its hands. Personally, I interpreted the Buddha as simply coexisting with the flower as opposed to protecting it. Furthermore, there is much juxtaposition between the ancient, faded nature of the statue and the vibrant details of the anatomy of the flower. For me, the choice to add the flower (one made by Jim Ede himself) allows for an observable connection and contrast between art and nature – the harmony between which being the very concept this exhibit explores.

Examining the preserved hairy-nosed otters within the jar made me think about the hidden side of presenting and storing specimens within a museum. The method of preservation of specimens within a spirit allows for surface level observation of the animal, reflecting pretty exactly how the creature would exist naturally. I feel this can be observed from my chosen specimen especially as the scene captured seems like a snapshot of an intimate moment between two delightfully adorable otters. However, this scene is not as effortless as it appears: it takes human intervention to preserve these specimens as such. To prevent decomposition, the chemical formalin must be injected into the specimen to ‘fix’ its cells. This complex process exemplifies the human action and choice necessary to present natural objects within a museum.

The complicated connection between man and nature is explored within both of my chosen objects, it is the common thread which links them together. The Buddha and its flower convey the contrast within such interactions while the otters detail how intertwined man and the natural world are – a link which is unavoidable in obtaining and presenting a museum specimen. Overall, these pieces (and the connection they represent) invite is to acknowledge and find balance within the complex relationship between humankind and mother nature.

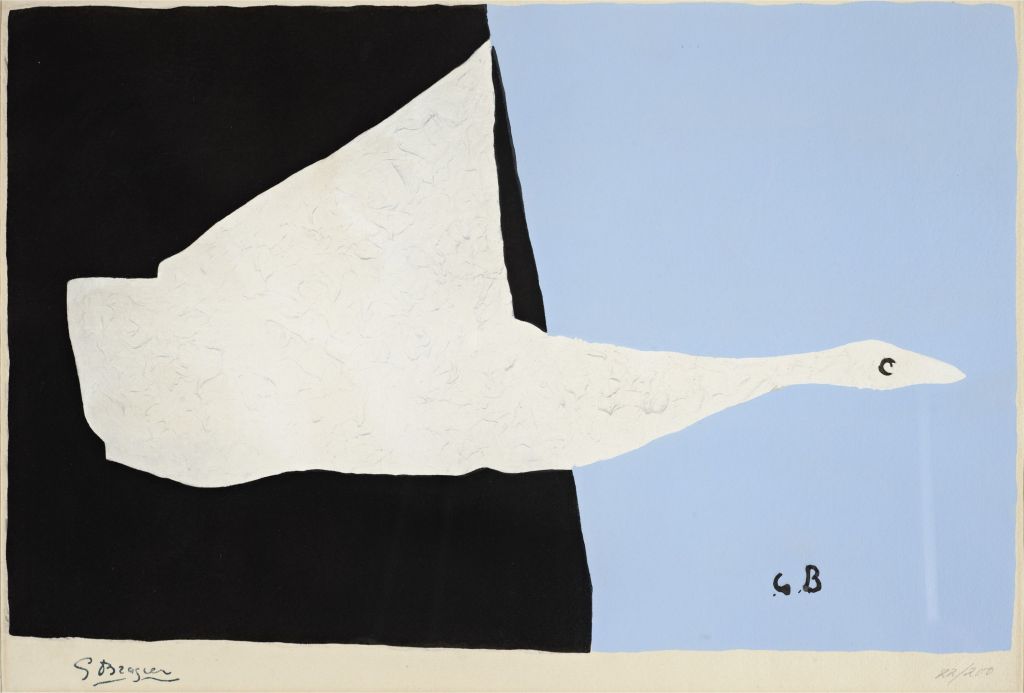

6. European robin and ‘Le Cygne Volant’, Georges Braque, 1950s late

written by Ameenah

Why do birds have wings? Is it coming through the dark? It is going into the hopeful light? A bird chases through the sky, from left to right. Birds – simple surface yet fractured harmony of intricacy within. Human intervention threatening its biochemical processes, it brings the question, do birds have wings to escape threatening humans? No clear distinction between wing and self, flight an integral part of its being. Past experiences woven deep within art. A solitary bird, carefully crafted to endure nature, much more than meets the eye. Can we use art to define birds and save them?

7. Western Parotia and ‘Flowers’, Christopher Wood, 1930

written by Chloe

Museums are made to teach us by storytelling. But humans have different perspectives and stereotypes that influence the way we present stories. These two objects: the birds and painting are impacted by human choice. The birds are displayed with the female below the male, looking up passively. A person chose to display these birds this way based on their own bias. The painting, symbolic of the beauty and feminine energy of nature, is placed below a window out of sight. The visitor must seek it out. Do you think the narrative of nature being feminine is true?

This artwork is positioned beneath a window forcing the viewer to look down and take in a new perspective. The painting depicts a vase of flowers framed by a dark storm like background of thick black and white brushstrokes as well as a black frame. The painting provides a clear contrast between dark and light bringing forward the relationship between light and the dark in our natural word and the harmony between the two. This juxtaposition also presents a depiction of life – the flowers, and death – the dark background as well as the blurring of the two offering an interesting thought how divided are life and death? Are they harmonious, only able to exist with the other? Similarly this can be applied to light and dark. Can they exist without the other and if not are they in fact inherently connected much like nature, humans and art. Humans have always lived and worked with nature and humans have always created art and nature has always informed art. So this painting is able to offer us an example of the connections between all things in life through its duality of light and dark, life and death. Also the painting could be interpreted as a depiction of femininity – the flowers are beautiful and if we place the narrative of nature being feminine onto this painting it can be seen as an attempt to hide feminine energy from the visitors of Kettle’s Yard.

8. Superb Lyrebird and Piano at Kettle’s Yard

written by Enoch

Reverberating notes caressing the ears of man below

Speaks to their heart a soothing tone

Is music actually food for the soul?

Yes, it is, in man’s abode.

Referred to as ‘masters of imitation’, the superb lyrebird can replicate most sounds they hear, marking their territory for their concert platform which attracts mating partners. This phenomenon accentuates the connection between art and nature. The lyrebird, nature’s artist, begs the question: which came first, bird song or human song? The piano in Kettle’s Yard emphasises music as a form of art. A way to feed the soul and portray your emotions without words.

Music, as a form of art, is a form of communication, without much use of words. Being the food for the soul, it provides therapeutic nutrients to recharge our psychological battery and feed the inner man with an insatiable thirst for spiritual and mental growth. The fact that we are what we eat further depicts our bodies as embodiments of music. Our emotions are also directly impacted, causing us to move/dance while listening.

9. Flame Bowerbird and ‘Chalk Window’, Cornelia Parker

written by Carmen

Despite initial differences you may observe, both pieces are connected by their contradictory nature. The chalk painted window (by Cornelia Parker) contrasts the shadows it casts upon the room, while the flame bowerbird’s fiery plumage juxtaposes the green of its environment: its need for survival clashing with its bright hue, shining nests and spectacular dancing skills. If art and nature can unite not only despite their differences, but because of them, perhaps there’s hope for humans to see beyond their differences, connect with the world around them, and begin caring for our beautiful and diverse planet.

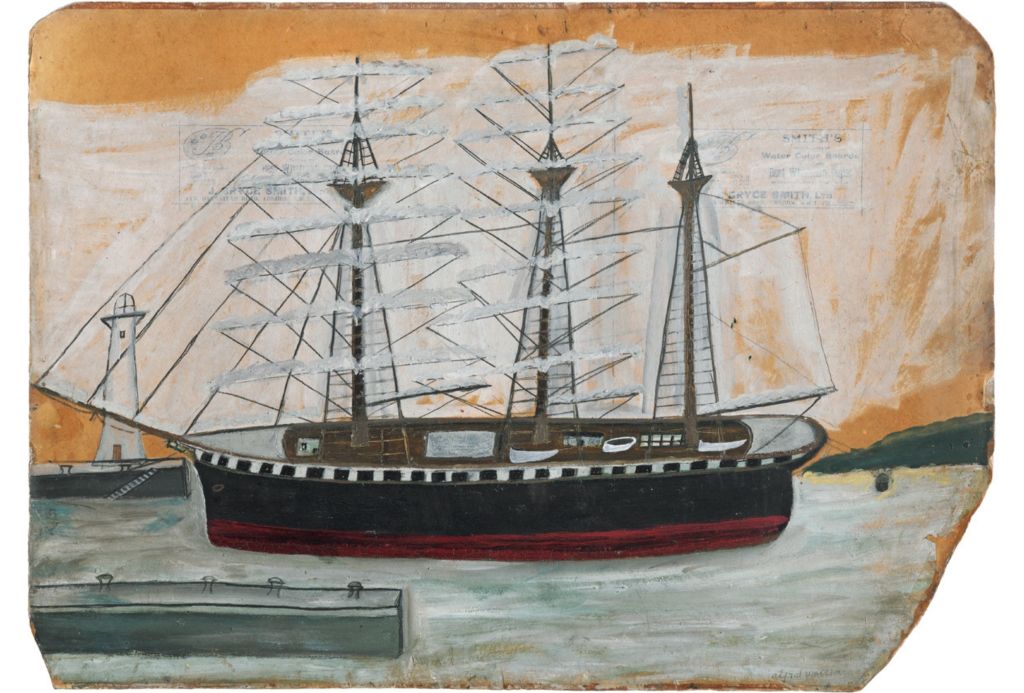

10. Satin Bowerbird and ‘Three-masted ship near lighthouse’, Alfred Wallis, 1928-30

written by Erika

These two pieces highlight the beauty of colour in both art and nature. The satin bowerbird uses vibrant blue to attract a mate, while the painting’s muted hues evoke calm and elegance. For animals, colour can mean survival; for humans, it stirs emotion. Together, they deepened my appreciation for the natural and artistic worlds – and left me wondering if we’ll preserve their richness for future generations.

11. Gharial and ‘Three Sailing Boats in a Line’, Alfred Wallis, undated

written by Sanya

Souls in Solitude. Alfred Wallis’ ‘Three sailing boats in a line’ is deceptively simple: muted tones, minimal detail, and placed at the back of Kettle’s Yard, away from Wallis’ other pieces, mirroring the quiet isolation of the boats it depicts. It suggests a peaceful yet lonely coexistence between humans and nature. Similarly, the critically endangered gharial leads a solitary life, now confined to just 2% of its historical range. Dam building, sand mining, and pollution have devastated its habitat. Wallis’ painting invites reflection, while the gharial’s story

demands action. Both are reminders of what’s lost when nature is left in solitude…

‘Three sailing boats in a line’ by Alfred Wallis is exactly what its title suggests. Yet, beyond its literal depiction, the painting feels like a personal reflection of Wallis’ deep connection to the natural world, shaped by his life as a sailor. Though the colour palette is muted and the design appears simple, the work leaves viewers with much to wonder. Its placement raises immediate questions: why is this painting displayed alone, away from Wallis’ other works at Kettle’s Yard? Tucked at the back of a room, it exists in quiet isolation, just like the three boats it portrays. The limited colour use is unusual for Wallis and might suggest a deliberate shift in tone. Is he capturing a moment of harmony between humanity and nature? Or is he portraying “Souls in Solitude”? Similarly, the story of gharials is one of isolation, inviting us to reflection our relationship with nature. Critically endangered since 2007, gharials now occupy just 2% of their historical range. Often overshadowed by their crocodile cousins, the few that remain are found between India and Nepal, leading solitary lives. Unlike Wallis’ painting, whose meaning is left to interpretation, the cause of the gharials’ solitude is painfully clear: human interference. Habitat destruction and pollution have driven their decline, and conservation efforts have so far failed to reverse the trend. Wallis’ painting and the fate of the gharials both convey solitude: one interpreted, the other very much a reality. While the painting reminds us that peaceful coexistence between the human-made and the natural world is possible, the story of the gharial serves as a warning. It’s up to us to reflect on our impact and act before more species suffer the same fate.

12. Shoebill and ‘Bird’, Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, c. 1913-14

written by Kasper

I want you to look at these side by side to see the similarity of natural form in art and nature and see the inspiration nature has on artists. The natural flows of the Henri Gaudier-Brzeska look to imitate nature and gives a very similar form to the natural anatomy of a shoebill. I want to show off the shoebill due to its unique shape of beak that allow it to produce a chattery sound that it uses to communicate. It is also hooked to allow for the killing of its prey (mainly fish but also baby crocodiles!).

13. Jacana and Crucifix Fish at Kettle’s Yard

written by Holly

These pieces may seem dissimilar, but both spark curiosity in the same way. The Kettle’s Yard piece’s oddness demands attention. It is a catfish braincase – but resembles a religious crucifix. Even alive, the catfish creates wonder – with its whisker-like sensory barbels and land movement capabilities. Similarly, the perplexing image of male Jacana birds carrying their young forces reflection. Their unnerving appearances cause unease – viewed as ‘unnatural’ while being entirely natural. This paradox challenges perspectives and individual’s definitions of art

and nature. Why do they create discomfort, even when part of balanced life? And is something natural also art?

14. Oilbird and ‘Dancer’, Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, 1913

written by Phoebe

The oilbird is a nocturnal creature with large feathers to support controlled flight in the tight spaces in the caves they live in. The dancer’s body echoes the lightness of the oil bird’s feathers – delicate and poised, full of potential motion. As the sun moves across the sky, her shadow dances across the wall: she can only be seen in full when enhanced by nature. The bird’s agile flight and soft plumage mirror the dancer’s grace, blurring boundaries between art and life. Together, they remind me of how nature and art interlace in a fragile harmony.

15. Hawaiian Goose and ‘Vexilla Regis’, David Jones, 1948

written by Amélie

Conservationists saved Hawaiian geese from extinction; an example of humans and nature working together to reintroduce harmony into the world.

The drawing I chose depicts the chaotic coexistence of humans with nature. Bursts of yellow and red amongst the grey capture how nature brings beauty to our mundane everyday. The dove speaks to the divine connections we can find through nature.

Both pieces are a testament to why we should protect the voiceless whether human or natural. We must conserve the sanctuary both art and nature provide. Both objects ask: can humans and nature continue to find a fragile harmony?

16. Horseshoe Crab and Light switch in Kettle’s Yard

written by Emaan

A light switch.

An intricate forgery of nature,

archaic in its design,

Yet paraded

Under a delicate glass casing.

In a roughly carved wall it lies,

Breaking away from the blank canvas

To reveal

A flush of red and blue wires.

Intertwined Ignorance.

An intricate light switch and a horseshoe crab; deliberately portrayed together to display their shared fundamental, and yet, hidden role in our society.

The switch: a vessel discharging light, the foundation of all discovery. Paired with Limulus polyphemus, its copper-rich blue blood used to test for bacterial toxins in various medicines. How many of us turn on the kitchen light on a groggy morning and take a paracetamol, exercising ignorance towards such complexities. Where would we be without these things, which feel so very insignifi cant in the course of a busy day?

17. Hose’s Langur and ‘St Edmund (found object)’, John Catto, 1975

written by Alayna

A tree struck by lightning, now shaped like an angel. A Hose’s langur embryo, mirroring our own. One formed by fire, the other by evolution – both transformed into art by nature itself. These shapes speak not just of biology, but of beauty; not just data, but design. They invite wonder, urging us to look closer. Stewardship becomes more than duty – it is a response to the sacred, a call to protect the fragile ecosystems that embody both science and art.

18. Paper Nautilus and ‘Ceramic Bowl’, Lucie Rie, 1974

written by Alexandra

The ridges of the ceramic bowl mirror those of the paper nautilus shell. These objects share themes of protection and comfort. The bowl evokes stability found in simple elements. The paper nautilus carrying its eggs and mate in its fragile shell reminds us that natural shelter is essential to life. Each individual organism encapsulates unique life in the same way that each art piece carries unique interpretations. The more we find solace in nature, the more we care about defending it against the climate crisis as we realise that when we destroy nature, we destroy what exists to protect us.

19. Ammonite and ‘Illustration to the Arthurian Legend: The Four Queens Find Launcelot Sleeping’, David Jones, 1948

written by Isabella

Ammonites mark an absence of shell, they are a shadow cast in stone. This visible absence has captured people’s imaginations, thought to be petrified snakes in the medieval period, while the name comes from the Ancient Greeks’ belief that they were the horns of the god Ammon. David Jones’ illustration depicts folklore as a doorway to the past and finds beauty in its mystery. The ethereal figures are lightly sketched, blending in with the background and fading out of view. There is a feeling of something which is both present and absent, lightly treading on history and the present.

20. Abalone Shell and Composition of Natural Items at Kettle’s Yard

written by Sumayyah

I have presented these items together because they teach us about the diverse unique beauty in the natural world. The abalone shells’ crystalline structure refl ects a shimmering rainbow, while the composition at Kettle’s Yard balances contrasting forms: light vs dark, smooth vs rough…

This shell protects the abalone, yet represents the fragile marine systems threatened by climate change. Kettle’s Yard’s items are nature’s art, their beauty appreciated but not protected by humans. Indigenous communities revere the abalone, using it in jewellery and religious ceremonies. We, the global community, should learn to protect nature and coexist with our environment around us.

21. Cook Shell and ‘June (Balearic Islands)’, Ben Nicholson, 1924

written by Petra

I felt drawn to the painting because I couldn’t figure out the meaning behind it and the shell by its story, being from the same voyage used to convince the King to colonise Australia. They don’t seem to have much in common, however they can be linked by their beauty. The value of shells is tied to their beauty as is sadly true for women. Both also have similar muted colours that blend in, signalling a desire not to stand out. The brown of the shell helps it camouflage, as the similar colours of the woman and background does for her.

Lower Gallery

22. Greater Bilby and Candleholder from Jim Ede’s desk

written by Emily

To me, comparing bilbies to a human-made candlestick shows the power of the natural world over humans. Nocturnal mammals have, for thousands of years, achieved what humans hoped to accomplish with the invention of candles – ‘conquered the night’. However, there is more to learn from bilbies: the tunnels they dig to live in are also places for compost to gather, returning nutrients to the soil and supporting plant life. Bilbies replenish the environment they depend on for survival. What if we too viewed nature, not as an endless resource to exploit, but as a living system deserving of respect?

23. Quoll and Cypriot jug, circa 700BC

written by Lana

Balancing the area where three edges meet this unknown circular form softens the harsh lines that surround it. Though its decorative lines remain unbroken, its ‘spout’ is not, placing it in the corner to balance the aesthetic of Kettle’s Yard. Just as the ceramic balances the room through its ‘fragile harmony’ the Australian Eastern quoll is broken between its scientific and common name, with scientific ‘vivernius’ meaning the western ‘ferret-like’ and ‘quoll’ from the aboriginal (Guugu Yimithirr language) ‘dhigul’. Forcing you to question: by removing the vase’s name and the quoll’s heritage, how far can something exist without a western definition?

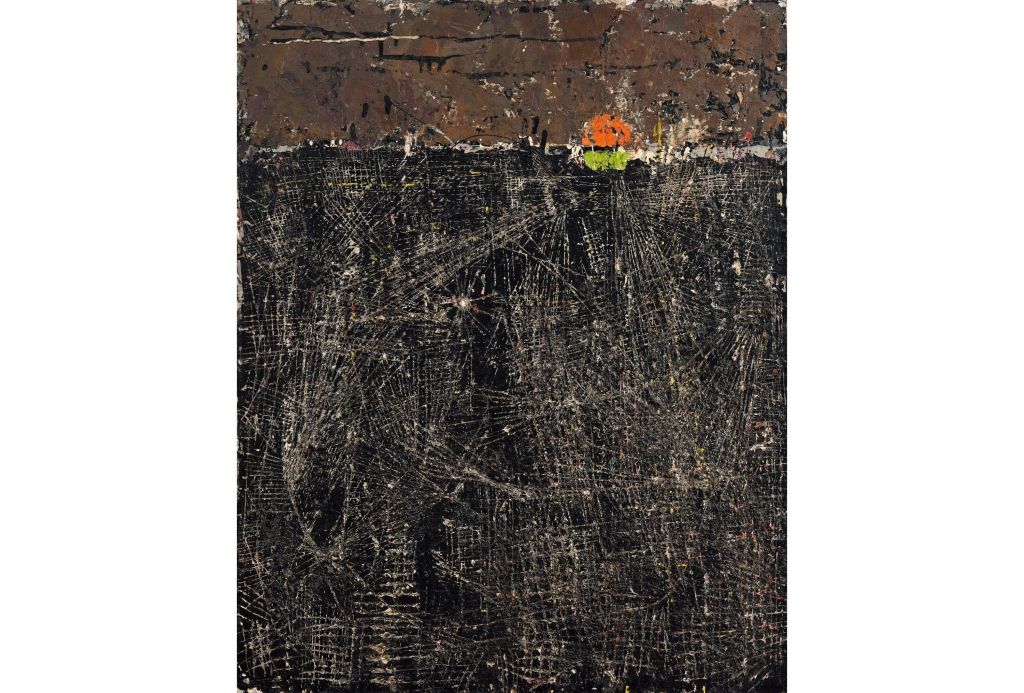

24. White Rhinoceros and ‘The Black City I (New York)’, William Congdon, 1949 (May)

written by Elise

In the darkness, look for the light.

Behold the dual nature of humanity. Hunted to the brink of extinction, this specimen was 1 of only 50 left in the world when shot.

Humans caused this catastrophe, but are also responsible for the white rhino’s resurgence to nearly 20,000 today.

Likewise, ‘The Black City’ represents a fragile harmony between society and nature. Created post war, it symbolises humanity’s potential for both destruction and creation: devastation is juxtaposed with a healing light, symbolising new beginnings.

Both pieces ask how much will humans destroy before making a stand and saying “let’s do better”.

25. Bittern and ‘Bird Swallowing a Fish’, Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, 1914

written by Diyaa

These two pieces of the bird swallowing a fish sculpture and the bittern symbolise the urgency of conservation. The sculpture represents the predator-prey cycle, a crucial balance in any ecosystem. Meanwhile, the bittern, once extinct in the UK, has reestablished here through conservation efforts in wetland habitats. Both made me reflect on the importance of pausing in both art and nature – taking the time to hear the distant call of the bittern. Similarly, art demands our attention for deeper interpretation. It led me to question: do we spend enough time recognising the delicate harmony in nature that we must protect?

26. Carrion Crow and ‘Guatemala’No 7 (Dying Vulture)’, William Congdon, 1957

written by Arthur

Both the carrion crow and the black vulture depicted in ‘Guatemala no 7’ are scavengers, meaning that they eat carrion (dead or decaying organic matter), along with fruit and insects for crows. Because of this and their black plumage, many people view them as deathly and dangerous, but both contribute massively to their habitats. owever, because of urbanisation, both animals are moving into these urban areas in search of discarded food and litter: because of the constant growth of structures, the patterns of the birds’ behaviour are changing and evolving at a rapid pace.

In this painting, mainly dark, monochrome colours are used, signifying the idea of death being a dark and frightening space. However, the first thing I noticed was the eye: it seems not to be staring at the viewer but into the far distance. For some, this suggests a sense of being scared or frightened, similar to how many people are similarly afraid of vultures, die to their association with death. However, you are able to faintly see the speckles of gold and white, associated with purity and some ideas regarding heaven: the artist may be suggesting that vultures are not the evil beings some expect them to be.

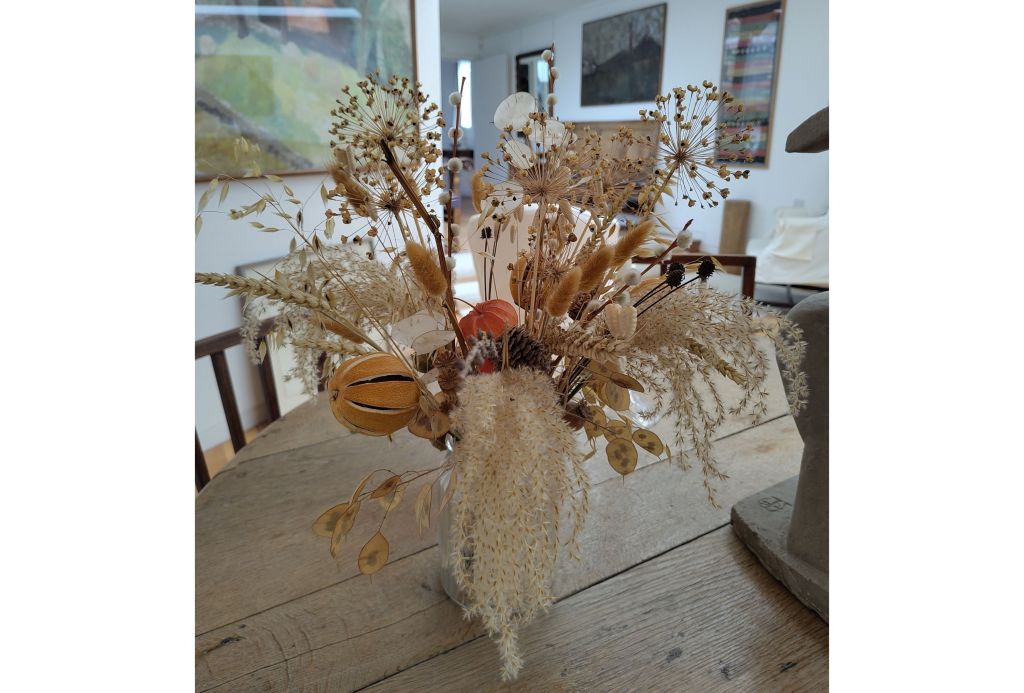

27. Hydrothermal Vent Chimney and Seedheads at Kettle’s Yard

written by Martha

Both these objects are linked by an undercurrent of hope and searching for life in unexpected places.

No sunlight, 400°C, high pressures… life seems unlikely around deep-sea hydrothermal vents, yet they teem with yeti crabs and stalked barnacles. Life has had to strike up a fragile harmony with this environment to survive.

Similarly, at first glance, these beige bushels of seeds appear unremarkable. However, they are capsules of possibility, albeit hinged upon a specific balance of water, space, and warmth.

To conclude, I ask you to embrace a difference perspective and ponder the ‘impossible’…

28. Smilodon and Flints in Kettle’s yard

written by Matěj

Both these things represent change. The flints, used by the indigenous people of Australia, highlight the change the human species underwent. The Smilodon also represents change as they went extinct as they simply did not change to adapt. Another reason is that the flints and the Smilodon are mysterious. It is unknown exactly where the flints come from and what the uses of the Smilodon’s canines were. They made me think about how balanced change must be to ensure both the survival of yourself and your surroundings. I wonder what the true stories are behind both specimens.

The reason I want you to look at these two things side by side is because they both represent change. The flints highlight the change the human species underwent to become what we are today. The Smilodon -Smilodon populator- too represents change, although ineffective change. This is due to the fact they went extinct, supposedly for many reasons. These include that they were better adapted for the ice age climate (which lasted until 11,700 years ago approximately, prior to their extinction), they were outcompeted and overhunted by humans or because as the ice age megafauna died out (due to climate change and/or overhunting), they simply did not have enough suitable prey to hunt and eat. In any case, they simply did not change to adapt.

Another reason is that both the flints and the Smilodon are shrouded in mystery. It is unknown what the purpose of the – up to 7 inches long – Smilodon’s canines was. A theory is that they were used for killing prey by biting onto their neck and suffocating them (similarly to lions) but there is no evidence that the jaws of the Smilodon could open that wide without dislocation. Another theory is that there Smilodon’s skull and neck muscles were adapted to deliver a slashing cut to its prey, causing a slow bleed out, although there is no evidence to support this. So, in the cases of the flints and the Smilodon, we rely, often wrongly, on assumptions and theories.

It made me think about how balanced change has to be to ensure both the survival of yourself and your surroundings. It made me want to ask, what are the true stories behind both of these things?

29. Giant Ground Sloth and ‘Maternity’, Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, 1913

written by Sarah

This sculpture by Henri Gaudier-Brzeska shows a mother cradling and protecting a child. It reflects on our human

instinct to care, and how we need to continue caring, not only for ourselves but for nature too.

The giant ground sloth’s extinction coincided with the arrival of humans in South America. Human hunting compounded the pressure of habitat loss due to natural climate change to the struggling sloth population.

Both skeleton and sculpture evoke our destructive and caring capacities, and highlight the need of protection for our environment and how we need to help onto our wildlife.

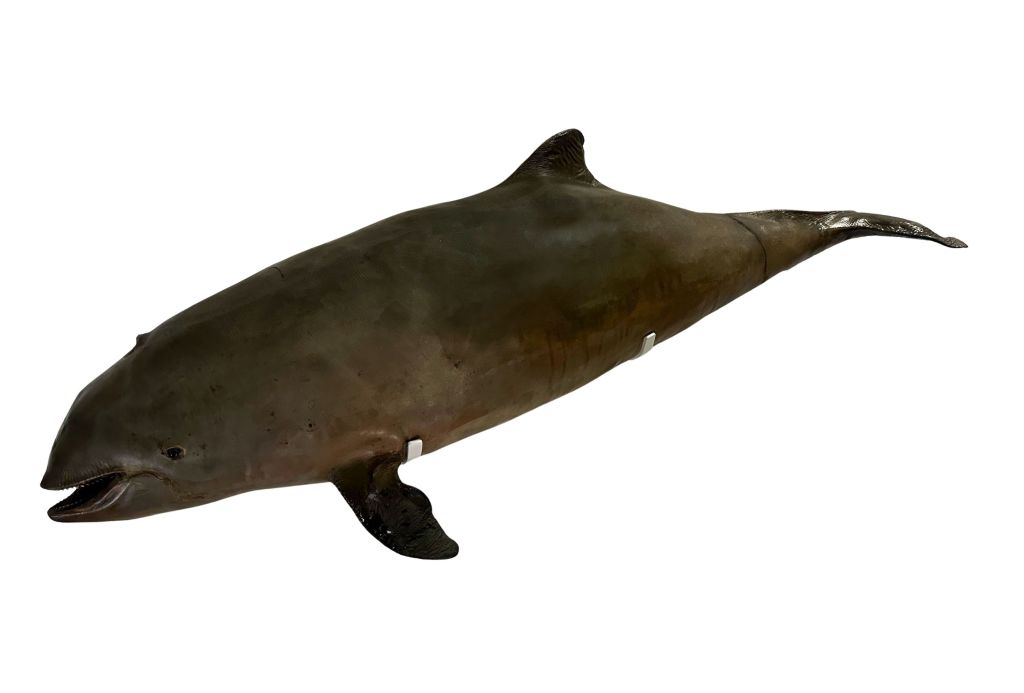

30. Harbour Porpoise and ‘Four Brass Rings and One Jade Ring’, Richard Pousette-Dart, undated

written by Jess

Harbour porpoises are the lesser known cousins of whales and dolphins. In contrast, the rings wouldn’t be complete without being next to each other. They, together, show the extremes of life – forever alone or forever in company. Without both of them and the balance they bring, life would be monotonous and boring. To me, they both symbolise the importance of balance and equality. Their differences should be accepted and better yet celebrated. Togetherthey raise a powerful question: how can we best fi nd a balance in our daily lives?