International Women’s Day Exhibition: Meet the Scientists

Opening on March 8th will be a special exhibition in the Museum galleries. Explore the Museum and find new labels written by some of the fantastic female scientists in and around the Department of Zoology. Find out about what they study and how, and be inspired by their work. This exhibition will run until the summer.

Upper Gallery

Aramish Fatima, Department of Zoology

I study the conservation of the Indian gharial, a critically endangered crocodylian native to South Asia’s river systems. Once widespread, their populations have drastically declined due to habitat loss, pollution, and resource competition. My work integrates species distribution modelling and genetic analysis to assess past and present populations and predict future habitat suitability. By combining ecological and genetic data, I aim to inform conservation strategies that support the long-term survival of this unique species, ensuring that gharials continue to play their vital role in maintaining healthy freshwater ecosystem.

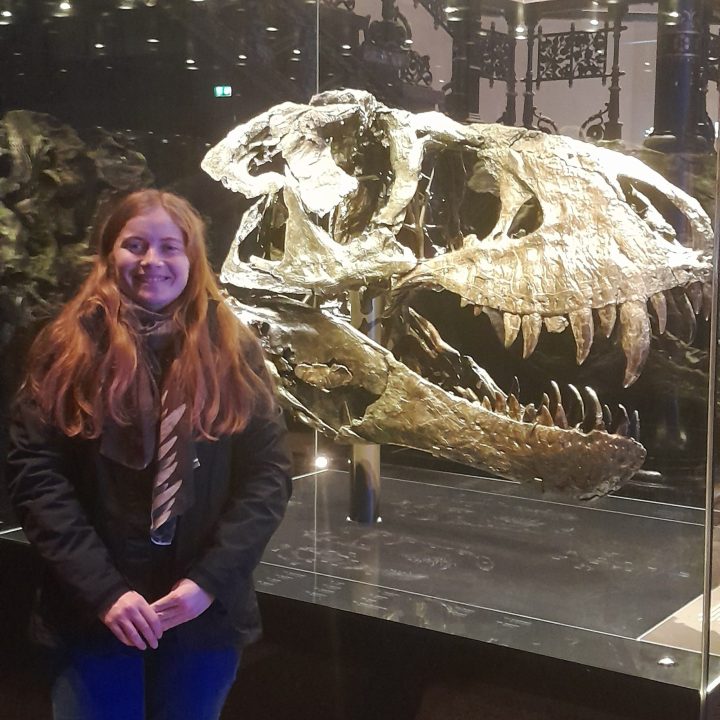

Annabel Hunt, Department of Earth Sciences

I study dinosaur skull anatomy for my PhD research at the University of Cambridge (supervised by Professor Daniel Field and Professor Steve Brusatte). My research involves using computed tomography (CT) scans to allow me to digitally peer inside dinosaur skulls and to examine anatomical features hidden beneath the external surface of the skull. I examine non-avian dinosaurs (such as the Tyrannosaurus rex I am pictured with) and birds (yes, these are dinosaurs!) to enable me to piece together the evolution of various aspects of the skull from extinct to modern forms.

Mairenn Attwood, Department of Zoology

I’m intrigued by how interactions between species shape evolution and ecology. My research focuses on fork-tailed drongos – birds with puzzling interactions. They’re incredibly aggressive (they’ll even beat up eagles three times their size) and often mimic calls of other animals. They seem to use these abilities to manipulate other birds into helping protect their nests. But simultaneously, they are manipulated by African cuckoos, which lay eggs in drongo nests. I work with a brilliant field team in Zambia to study drongo behaviour: monitoring nests, presenting 3D-printed bird models and broadcasting bird calls.

Maria Grace Burton, Department of Earth Sciences

I study one of the most fascinating traits of birds—their hollow skeletons. Unlike any other living animals, many bird bones contain air, a trait called ‘skeletal pneumaticity’. This helps birds adapt their weight for different lifestyles. For example, birds with more air-filled bones are lighter for flight, while those with fewer—like penguins or auks—have heavier skeletons for diving. By studying both modern birds and fossils of their extinct relatives, I trace how this unique trait has evolved over millions of years.

Dr Olivia Plateau, Department of Earth Sciences

With more than 11,000 species, birds are extremely diverse in terms of size, colour, shape, ecology, and habitat. I am an evolutionary biologist, and I have a particular interests in the morphology of bird skulls. Within the skull, I focus on an interesting functional grouping of five bones in the roof of the mouth, called the palate. Along with the beak, the palate bones play a major role in obtaining and processing food. My research aims to better understand the relationship between the morphology of palate bones and bird feeding ecology.

Dr Carla du Toit, Department of Earth Sciences

I am interested in how birds perceive the world around them using their sense of touch, and how specialised touch organs in their bills evolved in ancient birds. My research has shown that the ancestors of ostriches and emus had specialised touch organs that allowed them to sense vibrations in mud to find prey – much like modern day sandpipers and ibises can. We can identify these organs by the thousands of little holes on their beak bones, which you can see here on this ostrich’s bill. I’ve also recently discovered that penguins and albatrosses have specialised touch organs in their bills.

Prof Christine Miller, Department of Zoology

I grew up in Montana USA exploring the outdoors with my father. Wildlife such as grizzly bears, moose, and bison were my neighbours and snakes, ducks, and invertebrates were my companions. My love of the natural world led me to pursue studies in animal behaviour and evolutionary biology at University. I now run a research team, working on understanding the evolution of animal weapons, such as horns, antlers, claws, spiky legs, tusks, and spurs. We use the charismatic group of insects called the leaf-footed bugs to teach us how behaviour shapes these traits over evolutionary time.

Nynke Blömer, Department of Zoology

Since childhood, I have been fascinated by insects. After learning how to keep honeybees in my family apiary as a teenager, my eyes were opened to all pollinators. Now, I investigate how honeybees managed by beekeepers could affect bumblebees. I work with beekeepers in Cambridgeshire, and place bumblebee colonies in their apiaries to do field experiments. I track bumblebee colony nest development with the help of sensors that measure colony weight and temperature. I also study what honeybees and bumblebees eat by looking at the pollen they bring back to their nests.

Dr Adria LeBoeuf, Department of Zoology

How do our genes manipulate our social behaviour? This is the question that got me into science. I study socially transferred materials – things made in one body that get passed to another body, where they act. I study the proteins in these social fluids because they provide that link between genes and social life, and even further, because we can study their evolution. I mostly use ants study the evolution of social transfers because of their prolific diversity of social structures, but I am fascinated by all the incredible social exchanges across biology.

Sofia Dartnell, Department of Zoology

I study cuckoo bumblebees, a group of parasitic bees that rely on other species of bumblebee to survive. Unlike most bumble-bees, cuckoo bumblebees cannot produce their own workers or collect pollen effectively. Instead, they invade other bumblebee colonies, take over as queen, and use the host’s workers to raise their young. They need a strong population of host bees to survive. In a time of pollinator declines, cuckoo bumblebees face increasing risks. I work to understand their lifecycle, how populations sustain themselves over time, and whether their presence can indicate a healthy habitat for bumblebees.

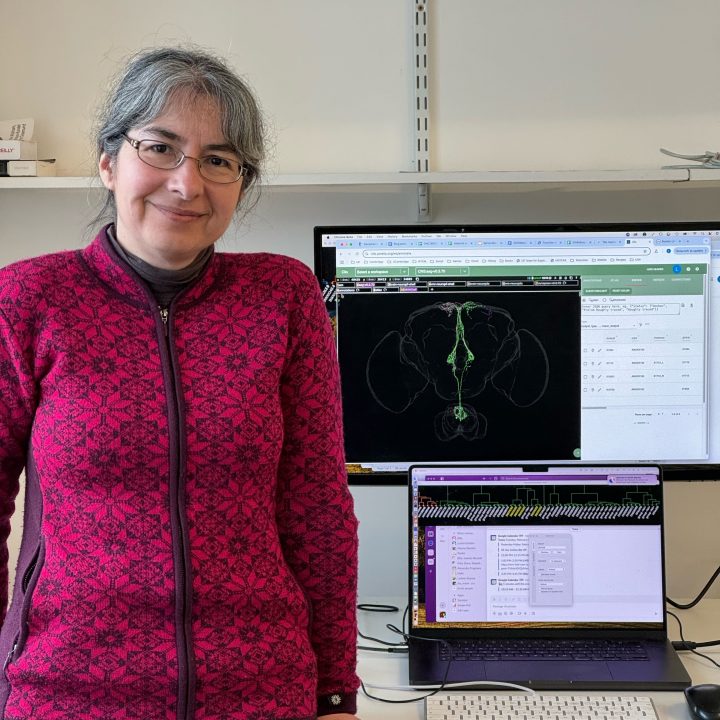

Dr Elizabeth Marin, Department of Zoology

I have always been fascinated by insects and kept them as pets as a child. At university, I learned to use the fly Drosophila melanogaster to identify genes used to build animal bodies, including those of humans. Later I studied the neurons that insects use to discriminate between odours and associate them with memories of pain or pleasure. I joined Zoology in 2017 to help create fly brain and nerve cord connectomes – detailed atlases of every neuron and how they connect to one another. Our online connectome datasets are used by theoretical and experimental neuroscientists all over the world.

Dr Tiffany Ki, Museum of Zoology

I am a conservation scientist interested in how we can use museum collections to investigate biodiversity change and inform present-day conservation. Despite much long-term human impact on the environment, biodiversity monitoring surveys were only set-up quite recently and only cover the past 40-50 years. Museum collections provide a rare opportunity to examine biodiversity change over much longer time scales (e.g. 200 years). I am currently working on examining two centuries of change in the UK macromoths and how it relates to anthropogenic changes (e.g. street lighting, land-use and climate).

Rosalind Mackay, Museum of Zoology

I am a Master’s student here at the University of Cambridge, studying insect conservation. My supervisor, Prof. Ed Turner, has a long-term project testing E-shaped earth banks called butterfly banks, to see whether they can help provide shelter for insects from climate change-related weather events. My project investigates how insects use the banks, and whether those living on the banks are different from those in the rest of the reserve. If the banks have all-round positive effects, they may be rolled out more widely to help mitigate the effects of climate change.

Rosa Pollard Smith, Museum of Zoology

I am investigating how we can manage nature reserves to help butterflies cope with high temperatures caused by climate change. Butterfly body temperature depends on the environment – if they can’t find cooler places during heatwaves, butterflies may overheat and struggle to perform important activities like feeding. I study how butterfly behaviour changes with temperature and test the potential of big E-shaped banks to provide cooler spaces for butterflies to function in nature reserves. By researching this kind of practical intervention we aim of provide evidence to guide butterfly conservation efforts.

Dr Emilia Santos, Department of Zoology

I am fascinated by Earth’s extraordinary biodiversity – its origins and evolution. My research explores how organisms function, diversify, and interact with their environ-ment. I focus on the cichlid fishes of Lake Malawi, where over 700 species have emerged in just the last million years. Despite their close evolutionary relationships, these fish have diversified dram-atically in their morphology, behaviour, and physiology. My research group investigates how genetic variation drives the development of these distinct traits, helping us understand the mechanisms behind such rapid and extensive evolutionary diversification.

Dr Rebecca Smith, Department of Zoology

Does helping toads across a road help increase their population? Conservation actions are often not as good as they need to be as information about which work (or don’t) is not used when deciding what to do. I manage the Conservation Evidence team. We find, summarise and make accessible scientific information about how effective conservation actions are, and help organisations use the evidence when planning how to conserve species or habitats. So far, we have summarised nearly 9,000 studies testing almost 4,000 actions. Our goal is for people to do more of what works and less of what doesn’t!

Lower Gallery

Antonia Netzl, Department of Zoology

I research vaccination strategies against SARS-CoV-2, the cause of COVID-19. SARS-CoV-2 is a virus that evolves, which means that it changes over time. These changes lead to its escape from immunity that was generated against a previous strain – the evolved strain is too different to be recognized by our immune system. To keep up with virus evolution, SARS-CoV-2 vaccines are regularly updated, similar to influenza vaccines. I study how our immunity responds to and changes with SARS-CoV-2 infection or vaccination, with the aim to improve future vaccines and better understand immune memory.

Dr Becky Heath, Museum of Zoology

In my research, I explore how tropical agriculture can benefit both people and the environment. A big part of my work is fieldwork—traveling to incredible places, working closely with Indonesian farmers, and measuring everything from crop success, to how quickly cow pats decompose, all to assess how sustainable their farms are. I also use cutting-edge tools like laser scanners, acoustic sensors, and camera traps to monitor wildlife (including birds!). The aim of my research is to understand this amazing region better and develop best-practice guidelines that enrich biodiversity in agricultural systems.

Sacchi Shin-Clayton, Museum of Zoology

I am a conservation ecologist, passionate about restoring our environment for a greener future. My field is full of exciting, ever-changing challenges as we balance forest conservation with agriculture. My work focuses on restoring and maintaining river forests within oil palm plantations in Indonesia, aiming to create a management system that supports both. While palm oil has a poor reputation, it’s one of the world’s most efficient crops, with immense potential for sustainable management—if done right. I’m excited to be part of a project that unites agriculture and conservation for a sustainable future.

Ella Carter, Department of Zoology

I am a Master’s student within the Kilner research group. This group consists of four postgraduate students, a postdoctoral researcher, and a group leader, all of whom are women. Our research focuses on the interaction between animal behaviour and evolution in burying beetles (Nicrophorus vespilloides). These beetles display remarkable parental care behaviours, including constructing a nest from carrion and feeding their offspring. I really enjoy working within such a welcoming group, where I am currently researching maternal influences on offspring interactions and morphology.

Dr Michela Leonardi, Department of Zoology

In my work, I reconstruct how climate changes impact species over long periods of time. For example, I have been studying the impact of the last Ice Age (peaking 21,000 years ago) on four European herbivores: horse, wild boar, red deer and aurochs (wild cattle, now extinct). I have also been working on prehistoric humans, asking similar questions, but the results are not published yet. The same methods that I use for the past can also help conservation: at the moment I am informing reforestation efforts in former war zones.