On the first Monday of October every year is World Habitat Day, a day set up by the UN to highlight the places where people live. At the Museum of Zoology, we like to look at the places where animals live – the amazing habitats from around the world. This year, we invited in members of the Young Zoologists Club to work with artist Marzia Falcioni to populate four different habitats with the sorts of animals that might be found there. We looked at our local fenland habitat, the African savanna, coral reefs and the ice floes of Antarctica. Onto beautiful backdrops created from collage by Marzia, the YZC members placed their collaged creations of creatures inspired by the Museum’s collections.

I love the ocean because it’s full of fascinating creatures.

Here is the inspiration from the Museum, and the results:

Fenland

We couldn’t talk about habitats without including one of the most important local habitats to Cambridge – Fenland. This wetland habitat is the most biodiverse in the UK. That is, there are more species recorded here than anywhere else in the country. Water is really important for wildlife, for more than drinking. If you’ve ever been pond-dipping, you’ll know that loads of creatures lurk beneath the surface of the water, from dragonfly nymphs and diving beetles to tadpoles and fish. Then there are the animals that feed on these. And the animals that feed on the animals that feed on these… And we haven’t even begun on the plants supported by wetlands.

I love the kingfisher because it’s bright and quick and colourful.

I love the dormouse because it is cute.

I found the birds very interesting because they came in all different shapes and colours!

I love the swan because it’s really pretty.

Here are a few of the animals on display in the Museum that you might find in fenland habitats:

Bittern, Botaurus stellaris

The bittern is a member of the heron family. It lives in reedbeds, where its mottled brown feathers keep it well hidden. Your most likely encounter with this cryptic bird is hearing the boom of a male calling. This low-frequency sound is so characteristic, we often refer to male bitterns looking to attract mates this way as ‘boomers’. The bittern population in the UK has been on a bit of a roller-coaster ride. They disappeared from our islands in the 1880s, thanks to people draining their wetland homes. Bitterns returned to the UK in the early 1900s, and by the 1950s there were around 80 booming males recorded here. But fastforward to the 1990s, and the population shrank again, with only 11 booming males recorded in 1997. A lot of work by conservationists to create the right environments for these enigmatic birds has seen an increase in their numbers, and there are now over 200 booming males recorded living in our wetlands.

Cuckoo, Cuculus canorus

Cuckoos have a fascinating life history. They are what is known as a brood parasite. This means that instead of raising their own young, they lay their eggs in the nests of other birds, leaving their hosts to bring up the chicks. The birds they parasitise are species like reed warblers and dunnocks – much much smaller birds than the cuckoos. And when you see the size of the chick compared with their foster parent, it does make you wonder how they can not see that the chick is not their own. Cuckoos are migratory, spending the winter in sub-Saharan Africa and arriving on our shores in April/May to breed. Their familiar ‘cu-ckoo’ call is traditionally seen as one of the signs of Spring in the UK, but it is becoming less and less common. It is in places like Wicken Fen that you can still hear their haunting calls.

Dragonflies, Order Odonata

There are many insects that benefit from there being lots of water around. Dragonflies and damselflies, the group of insects known as the Odonata, are just such a group. As adults, these insects are agile fliers, often with large wingspans for their two pairs of veined, transparent wings. They are predators, with large compound eyes appearing to form much of the head. Then there are the vibrant emerald greens, azure blues and even red of many species. Rivers and streams are good hunting territory. But did you know that they lay their eggs in water? And when those eggs hatch, the larval forms stay underwater, growing into ferocious predators of aquatic creatures themselves, and breathing through gills. When the time is right, the dragonfly larva sit near the edge of the water, starting to breathe air and getting ready for their final moult. When ready, they climb onto a suitable piece of vegetation above the water, and moult into their adult, winged form.

African Savanna

Walk down to the lower gallery of the Museum and you will find yourself surrounded by forest of skeletons, many of them belonging to animals of the African savanna. This habitat is a warm, open grassland peppered with trees. Think of the grasslands of the Serengeti. Some of the animals we see there include lions, elephants, giraffes, hippos, rhinos…

I love the African elephant because it’s really cool.

I loved the pangolin because it’s the only mammal with scales.

Here are a few on display at the Museum of Zoology:

Giraffe, Giraffa camelopardalis

The giraffe is the tallest land animal alive today. Take a look at our skeleton, and you can see where the height is coming from. It is a big animal, but its neck is extraordinarily long. Count the number of bones in the neck, though, and you’ll find the same number as we have – seven – they are just a lot longer. That’s not the only source of the extra inches. Take a closer look at the legs, and their proportions are completely different to ours. The bone at the top of the leg (the femur in the back leg, humerus in the front) is short compared to the length of the leg as a whole. The knee and elbow are only just below the level of the bottom of the ribcage. The big joints in the middle of the legs are the ankle in the back leg and writst in the front. Yes, that means about half the length of the leg is actually the foot, with the giraffe standing on the tips of its toes.

Lion, Panthera leo

Think of a top predator on the African plain, and chances are you’ll be thinking about a lion. Perhaps a male lion, with its thick mane around its neck? The skeleton on display is of a female lion, or lioness, and although they may not look as impressive, they are usually the ones to hunt and capture food for the pride. Lionesses are known to work together as a team to bring down larger prey. Lions have some fearsome adaptations for the hunt – from big teeth and powerful muscles to retractable claws to help grip the ground when on the chase (amongst other things).

Aardvark, Orycteropus afer

Something a little smaller now, the nocturnal Aardvark. This mammal comes out at night, spending the daylight hours in burrows in the ground. The name ‘Aardvark’ comes from the Afrikaans word meaning ‘Earth Pig’, and taking a look at its snout you can see where this name came about. Aardvarks have large claws, but these are for breaking into termite mounds and ant hills rather than slashing at larger prey. They have a very long, sticky tongue which they use to lap up hundreds of insects a night.

Coral Reef

We had to include an underwater habitat in the list, and with so many nooks and crannies and variations, it had to be a tropical coral reef. Although they may not look at at first glance, corals themselves are animals. In the Museum, you can find the ‘skeletons’ left behind by colonies of coral polyps. When these animals were alive, they would have been a riot of colours. These colours come from tiny, single-celled beings called zooxanthellae (pronounced zoo-zan-thell-ee) living inside the corals. Like plants, zooxanthellae can use the energy of the sun the make sugars from carbon dioxide and water – a process called photosynthesis. Thse corals form microhabitats for lots of other animals too.

I love the coral reef because the wildlife is interesting to look at.

I like the turtle because it plays a crucial part in the ecosystem.

I loved the coral reef because they have lots of colour and many animals live there which are tropical.

Here are a few of the animals from coral reefs that you can see on display in the Museum of Zoology:

Grooved Brain Coral, Diploria labyrinthiformis

The largest of the stony corals on display in the Museum is this specimen of a brain coral, and you can see where it gets its name – the pattern on this ‘boulder’ look just like the folds in a brain. This skeleton was not made by one animal, but by a whole colony of thousands of polyps. The individual polyps of a brain coral are not in their own individual holes in the skeleton. Instead, their bodies are much more closely connected, and this is why it looks like long channels covering the surface of this coral instead.

Giant Clam, Tridacna gigas

This huge shell belongs to the largest species of bivalve mollusc today. When it was alive, the shell would have been filled with soft tissues – muscles to open and close the shell, gills to breathe and filter feed, a mantle to lay down the shell… Like the corals on the reef, giant clams host zooxanthellae in their soft tissues. These tiny, single-celled organisms provide the clam with some of the food it needs, and can give the animal inside the shell beautiful shimmering green and blue colours.

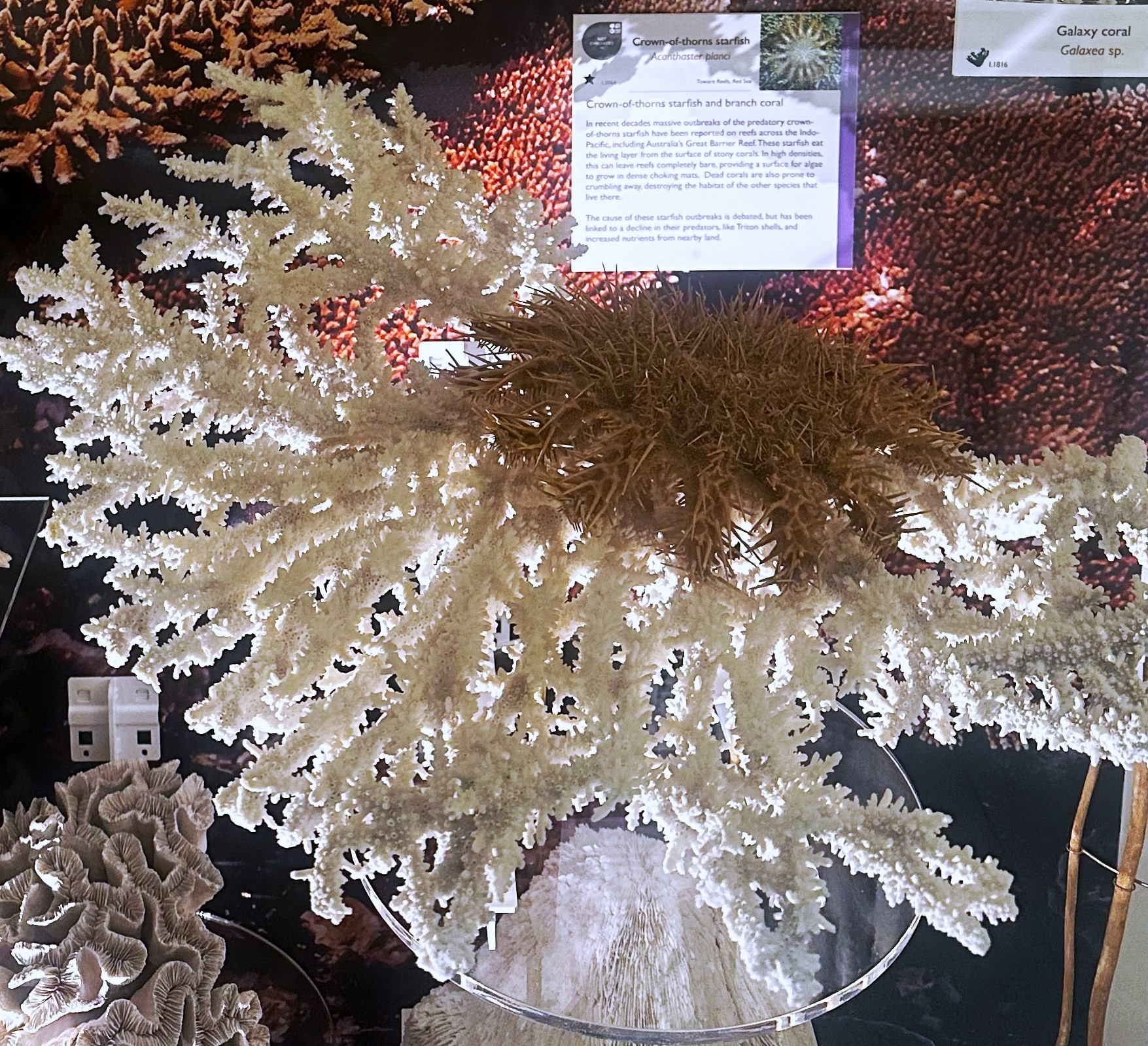

Crown of Thorns Starfish, Acanthaster planci

Our last coral reef profile is of a coral predator, the crown of thorns starfish. Can you spot it on the coral skeleton on display here? These starfish can have up to 21 arms, and are covered in venom-tipped spines. But it is their feeding habits that are causing issues for coral reefs. The mouth of a starfish is on its underside. The crown of thorns starfish feeds by pushing its stomach out through the mouth so that it covers the coral it wants to eat. The digestive juices the stomach produces then get to work on the coral polyps, breaking them down for the starfish to absorb. Crown of thorns starfish numbers can get out of hand and have a devastating effect upon coral reefs. This is becoming more of a problem, but the reasons are complex, including the removal or predators and increased survival of crown of thorns starfish larvae, and are being studied to try to save coral reefs from excessive damage.

Polar: Antarctica

The polar regions of the Earth are the areas around the North and South Poles. Here, the sun’s rays are weakest and the temperatures are coldest. The area around the North Pole is called the Arctic, and it is an ocean surrounded by land. But we chose to focus on the area around the South Pole: the Antarctic. Here we have a continent of land – Antarctica – surrounded by ocean. Antarctica is home to the coldest place on Earth, where temperatures can drop below -80oC. While some things do manage to survive on the Antarctic continent, it is the oceans around it that are teeming with life, from giant sea spiders and sea urchins to seals, whales, penguins and other sea birds, to name just a few.

I saw the antarctic and Ilove it because it’s got seal in it and I LOVE seals.

I love the penguin because it’s a very good swimmer and it’s my Favourite Animal.

I love the leopard seal because he looks so cute.

I liked the little blue penguin, because it’s so small and cute.

I love the petoel because it lives in Antarctica which is really cool.

Here are just a few of the animals you can see from the Antarctic on display in the Museum of Zoology:

Emperor Penguin, Aptenodytes forsteri

Huddled on the Antarctic continent over winter, keeping warm against the cold cold winds, male emperor penguins are holding eggs on their feet to keep the developing chick inside from freezing. Emperors are the largest of all species of penguin alive today, and the only species to breed on the Antarctic continent itself. While the males are waiting inland over winter, the females are returning to the sea to feed, food which they will bring back for their chicks once they hatch. Emperor penguins cannot fly, but their flipper-like wings are perfect for swimming through the sea in pursuit of fish to eat. They have a thick layer of blubber under the skin to keep warm, and have specialisations of the blood vessels that mean that heat is transferred to blood going back towards the body’s core rather than losing it through toes and wing tips to the freezing environment around them.

Leopard Seal, Hydrurga leptonyx

Leopard seals are the only seals to hunt warm-blooded prey. Yes, this is a species that eats penguins. But it is not the only diet of this formidable predator. Take a look at its teeth and you can see large canines and sharp incisors at the front are used to grasp and tear apart larger prey, like penguins and other seals. Further back in the mouth, the molars have a very complex shape – each with three peaks on a mountain shape. They upper and lower molars meet in an interlocking pattern that creates a sieve, perfect for filtering krill (a shrimp-like crustacean that lives in giant swarms) out of the water. Krill makes up a large part of their diet. Maybe you’ll see the toothy grin in a different way when you next visit the Museum.

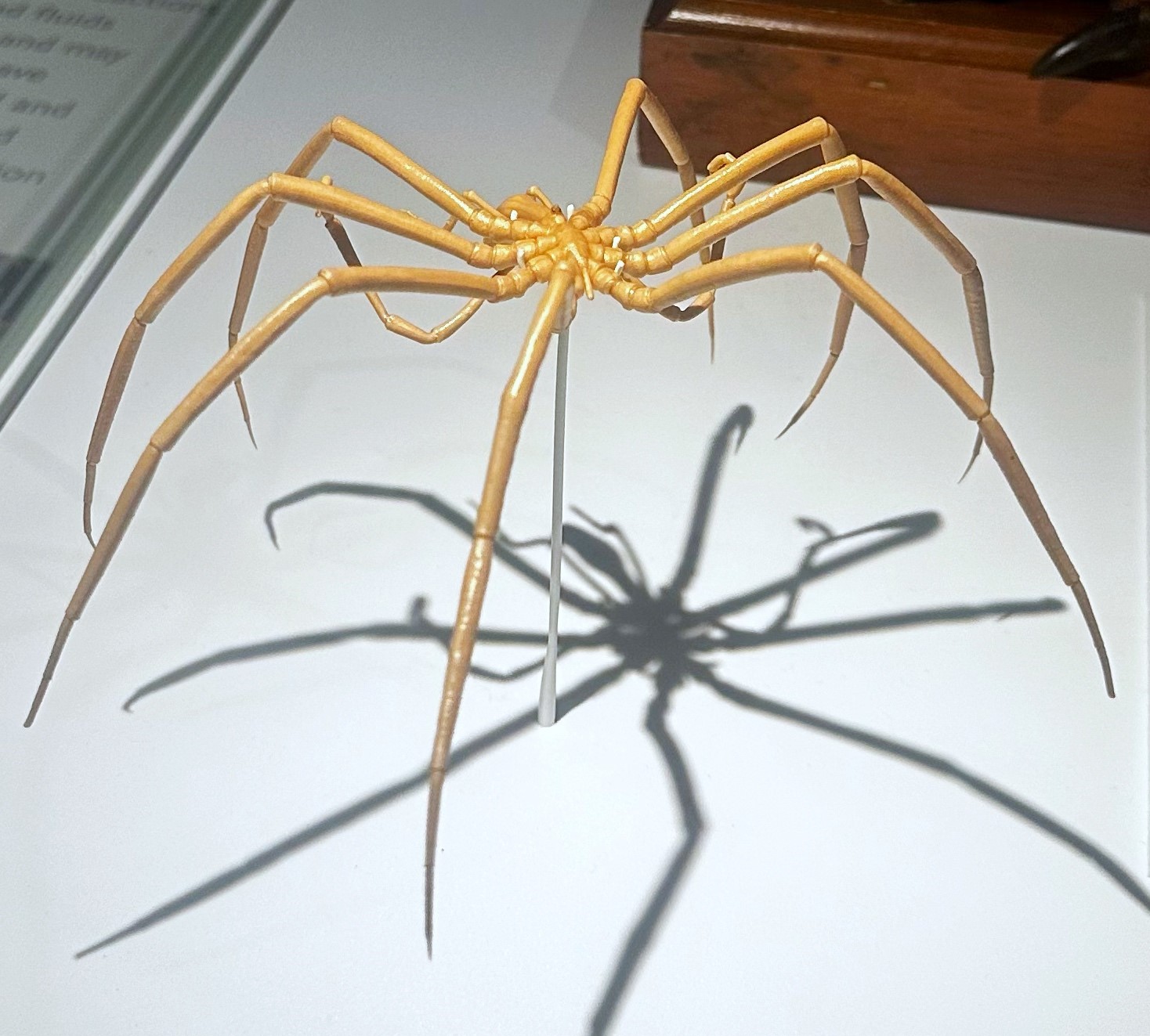

Antarctic Sea Spider, Colossendeis macerrima

Sea spiders are not true spiders, but have their own group within the arthropods called the Pycnogonida. But like spiders, they have a pretty ferocious way of feeding. When they find a tasty prey item, something nice and soft-bodied, they plunge their straw-like proboscis in and suck out their insides. We get sea spiders across the world’s oceans, but seldom do they reach the size of this one from the Southern Ocean. There are lots of polar animals that are bigger than their counterparts in warmer waters. There are several theories as to why this might be – it could be the higher oxygen levels in cooler water, or the chemistry of the seawater here, to describe a couple of possible explanations.

I love the ocean becasue of all the fascinating wildlife.

I love the dolphin because it’s beautiful.

I liked the common vampire bat because I like the texture of the wings.

What can we do to protect our local habitats?

At the end of the art workshops, the members of the Young Zoologists Club were invited to suggest things we can do to protect wildlife and habitats. Here’s what they said:

Do not litter

Tell people to stop deforestation! Make more protected land!

Stop littering the sea

Less pollution

Stop cutting trees down

Do not poach

Do not waste water

Pick up rubbish

Drive less

WE can make wild corners and stop littering.

Less light and noise pollution.

Re-use stuff.

I want to protect a rhino

We can create protected land.

Make a bug hotel. Plant flower they like.

SAVE OUR RIVERS. Sewage is being dumped into our rivers so change our sewage treatment

It doesn’t have to be a big thing. Every small thing helps our world.