In April 2024, a group of 29 Year 12 students from schools and colleges across the UK attended a residential programme run jointly between the Museum of Zoology, Clare College and the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology to create a temporary exhibition for display in the two museums. Trodden Earth was the result. The title and all the text you can see on the blog post was written by the students. They chose the theme of the exhibition, its contents, and worked with graphic designers from Paper Rhino to create its feel and identity. The exhibition is on until the end of 2024, so do come and see this fantastic work in situ.

We would like to thank the Isaac Newton Trust’s Widening Participation and Induction Fund to supporting this project, Paper Rhino for their work turning their ideas for the logo and visual identity of the exhibition into fantastic graphic designs, and the Botanic Garden, Herbarium, University Library, and the Women’s Art Collection at Murray Edward’s College for welcoming us into their collections for inspiration and ideas.

Now over to the students, the Cambridge Future Museum Voices:

Trodden Earth

How do you feel about nature? How does nature feel about you? Is the loss of biodiversity due to climate change inevitable? Do you think there is hope for our planet?

Welcome to the world of uncertainty where we are going to question our significance as we explore the power dynamics of the natural world. For centuries we have exploited the power we have over our environments, bringing destruction and chaos across all corners of the animal kingdom. Human health and happiness relies on nature, but now, more than ever, it is the natural world which depends on us for its survival.

Take a step back into history and a leap into the future to see how our lives are evolving with our environment. Through showing the impacts that people have on nature, this exhibition aims to encourage people to use their relationship with nature for good, while inspiring hope for the future of the natural world.

Museum of Zoology: Upper Gallery

Large blue butterfly

by Amos

The large blue butterfly has a story of disaster and hope. Its caterpillars use their appearance and chemical signalling to attract red ants Myrmica sabuleti. The ant species is tricked into taking the caterpillar to its colony where it spends most of the year begging for food or eating the ants’ larvae until the caterpillar is ready to pupate into a butterfly.

Unfortunately, the reduction in close-cropped grassland area, the ant’s habitat, as a result of reduced livestock grazing, has affected the large blue’s breeding, causing it to go extinct in the UK in 1979.

Scientists reintroduced the large blue to the UK in 1983, and since then protected the habitat for the ants. Recently, the butterflies have had their most productive year of the last 150, giving us hope for the future.

Cowrie shells

by Grace

Adorning now the fashion and hairstyles of pop icons such as Beyonce and Alicia Keys, these small, oval shells have an interesting history of being used as a currency for trade in Africa, Asia, Oceania and regions of Europe. Their shape and size make them easy to be weighed and counted to determine value, whilst also being impossible to counterfeit. The oldest traces of use have been unearthed in China from the 14th Century, and served as a currency in some cultures until the 20th century. This is one of the first examples of nature being used as a currency for humanistic purpose of trade and commerce over their predominant natural purpose. To reflect, how is nature being used as a currency in the modern world?

Coral reef catastrophe

by Gerrard

Coral reefs are underwater ecosystems made up of corals in the class Anthozoa and phylum Cnidaria. First appearing 485 million years ago and a habitat for 25% of marine species, coral reefs are massively important. Corals get their colour from photosynthetic, single-celled zooxanthellae in coral tissue. We have lost 14% of coral reef areas since 2005, a situation worsened by coral bleaching, which is when zooxanthellae in coral tissues are expelled due to extreme temperature-changes – this has been worsened by climate change. We need to address this and, luckily, you can help contribute to the work already starting to get our coral reefs back. You can work with climate scientists to reduce our impact by using public transport, eating less meat and being energy efficient.

Quetzal

by Lily

The quetzal is the national bird of Guatemala due to its vibrant colour and cultural significance to the Maya. Local tradition considers it a symbol of freedom: local people believed it preferred to die of hunger than live as a prisoner. Their resplendent green feathers were used by the Ancient Maya to create diadems worn only by royalty. Occasionally, their feathers were used as currency due to their preciousness. Because their long green tail feathers were considered a characteristic derived from reptiles, they represented a link between bird and snake and therefore a link between heaven and Earth. For this reason, many Mayan languages also use ‘quetzal’ to mean ‘sacred’ or ‘consecrated by the gods’, specifically associated with the wind god, who shares their name, Quetzalcoatl.

Rodrigues solitaire

by Erin

The Rodrigues solitaire was a rather unassuming bird, with grey and brown feathers and a black band round its neck. But this bird has a very important story. A close relative of the dodo, the Rodrigues solitaire faced a similar end, almost 100 years later. The island of Rodrigues was colonised by French Huguenots in 1691, and by 1760 the solitaire was already extinct. They were fiercely hunted as food, and their eggs destroyed by cats, rats and pigs brought over by sailors. Rodrigues Island is close to Mauritius, home of the dodo, and the two birds’ stories teach that we must learn from our mistakes, or history is doomed to repeat itself.

Museum of Zoology: Lower Gallery

Numbat

by Rohan

The only marsupial among Australia’s diverse array that eats termites, numbat numbers are rapidly sinking. Our past reveals our dark secrets and exposes our guilt, as the foxes and cats the British brought over to Australia during colonisation directly influenced numbat decline. Not only will we lose such a beautifully distinct creature, we also are uncertain of the possible implications this will have on our lives too. Food, resources and farming are just a handful of potential human necessities we may be putting on the line. We tread and share the same path as all other creatures on our planet, and so we have the responsibility, and more vitally, the power, to tip the scales back into balance, rightfully restoring all we’ve taken for our sake but more importantly, theirs.

Tasmanian devil

by Elliott

Tasmanian devils are the world’s largest marsupial carnivores. “Devils” as they are frequently referred to, have a declining population, mainly due to a rapidly spreading contagious cancer. Devils were originally found in mainland Australia as well as Tasmania, but were outcompeted by the introduced dingoes, resulting in their eradication. Also, as scavenger animals, devils are often drawn to the site of roadkill for food. This results in many devils being killed in traffic accidents. Devils are now considered endangered, with a total population of 25,000. Fortunately, a collaborative programme between the government of Tasmania and the Zoo Aquarium Society has resulted in the creation of a captive population of devils, in an effort to amend the previous failures of humans, and prevent the very real possibility of devils’ extinction.

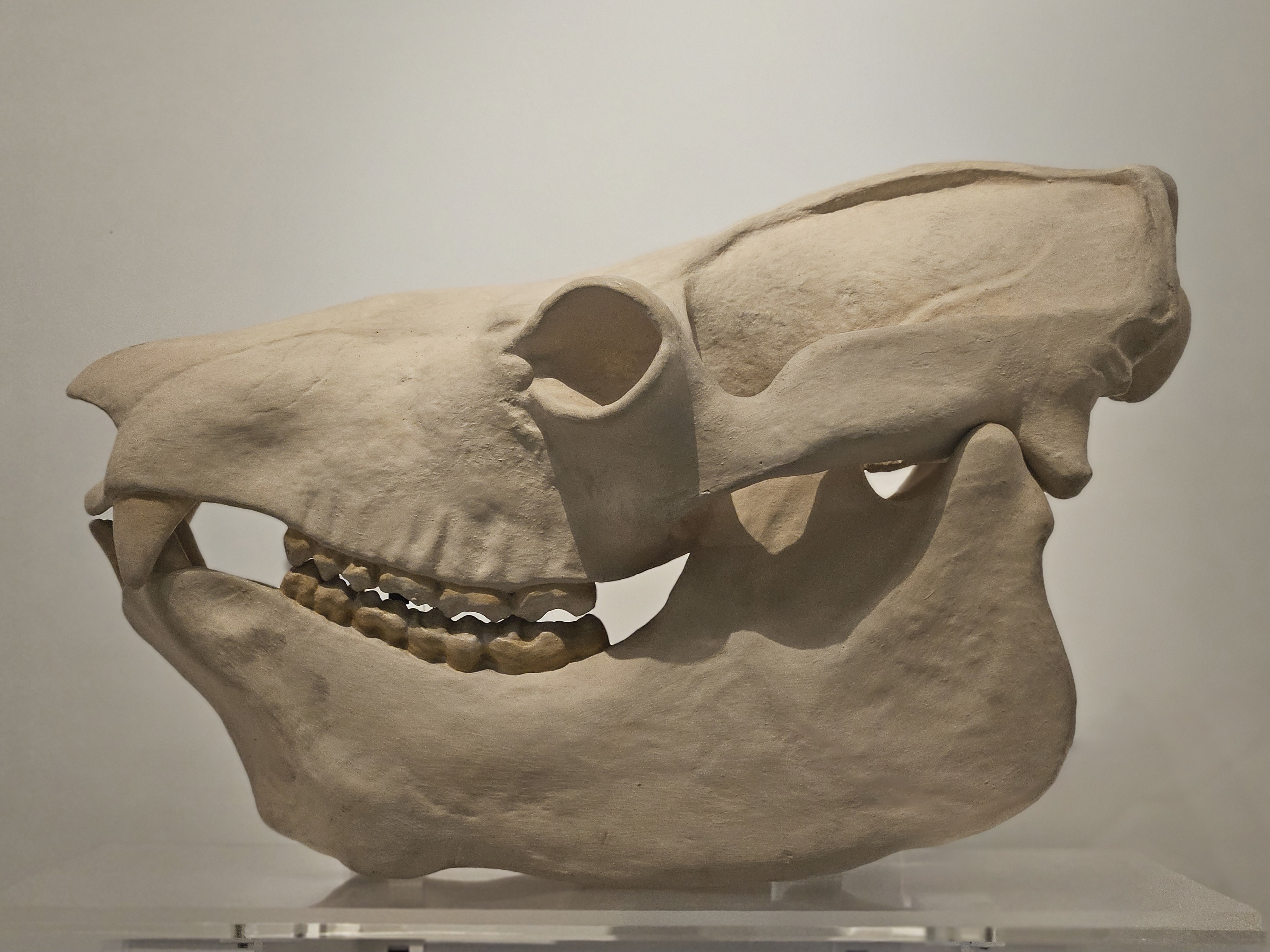

Koala lemur skull-cast

by Kizzy

The koala lemur was a slow-moving primate that weighed between 50-80kg – around five times larger than koalas (which are marsupials, so are not closely related). The ancestors of lemurs came to Madagascar around 35-60 million years ago on floating rafts of living vegetation across the sea from mainland Africa. Humans arrived on Madagascar around 2,000 years ago, and cleared vast areas of forest using slash-and-burn techniques. Unable to adapt to the changing environment, and with massively damaging overhunting, koala lemurswent extinct around 500 years ago. In the 2,000 years humans have been present on Madagascar, at least 17 species of lemur have been driven to extinction. Currently, of the 107 lemur species that still exist, 103 are threatened by extinction.

Bears

by Nusaybah

Bear bile has been used in traditional Chinese medicine for hundreds of years. Modern research has confirmed its antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory and hypotensive effects. However, bear bile has been marketed as a cure for cancer, colds and hangovers despite there being no supporting evidence for these uses. In the 1980s, the People’s Republic of China established bear farms where over 7,000 bears were kept in small cages and the bile extracted painfully and extremely inhumanely. As a result, many died from chronic infection and liver cancer. The trade of bear bile is lucrative and increases the threat to wild, endangered bears. To combat this, artificial bear bile is being researched. However, exploitation of bears is a problem of history, culture and economy so conservation efforts must be expanded upon.

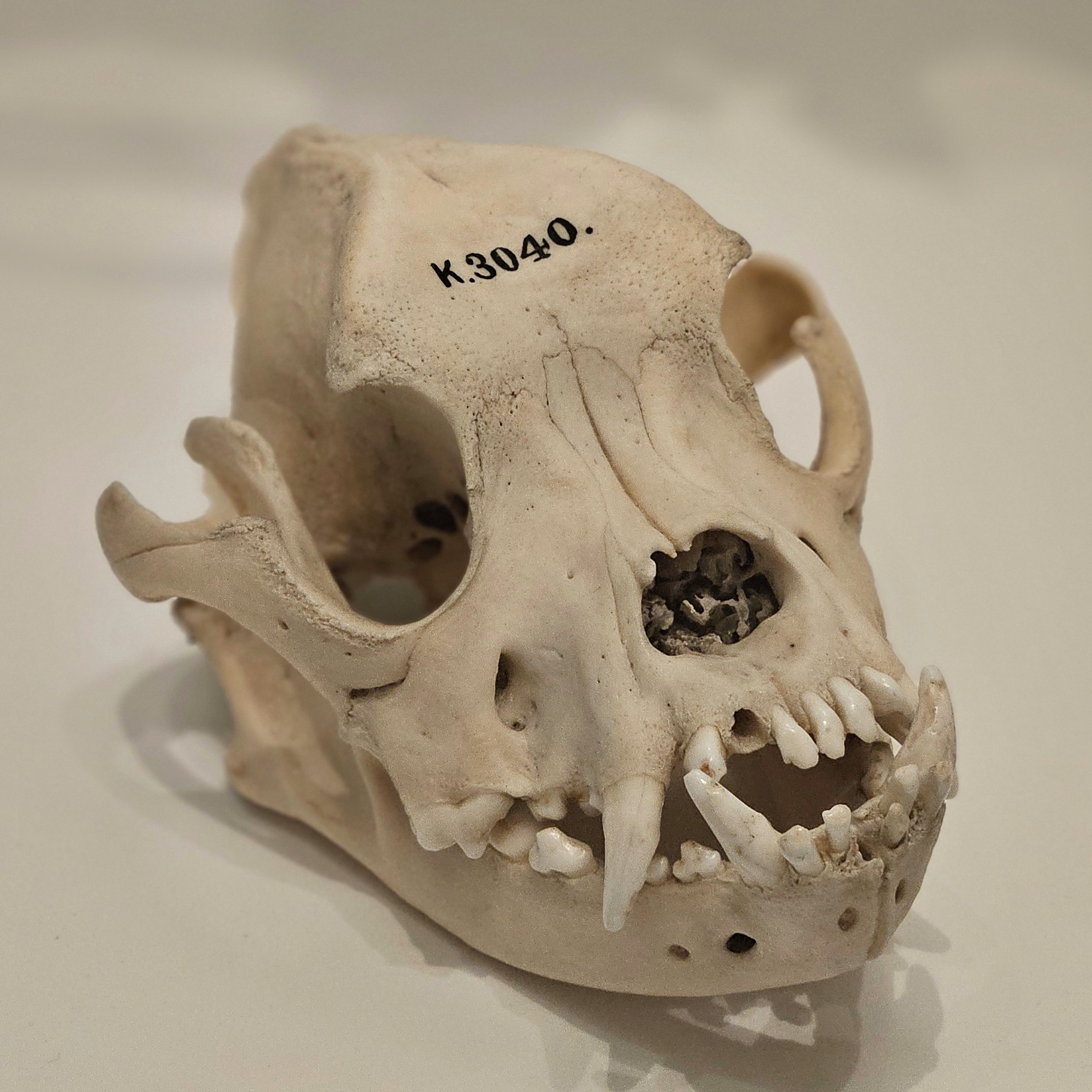

Bulldog skull

by Shenay

Bull dogs are well known for their shortened facial appearance and flattened noses. While some may think this is natural, it is actually the result of selective breeding and causes respiratory issues often requiring surgery in later life. Humanity feels that it can ‘play God’ for its own benefit with no regard for the species that we are affecting. However, we do have capacity for change, and we can see this in the Netherlands. In 2014 the Dutch government put legislation in place to ban the breeding of short-nosed dogs Put into practice in 2019, dogs are now graded on a traffic light system based on the length of their nose, encouraging the re-introduction of the species’ naturally longer, healthier noses and ending the suffering we have caused.

Western European Hedgehog

by Scarlett

The western European hedgehog, native to the UK, is one of the small number of mammal species covered in spines. Hedgehogs in the UK have declined in population by 30-35% since 2002 mostly due to habitat loss from farming changes, challenges of city landscaping and decline in woodlands. providing shelter and food, or creating hedgehog holes in urban areas to allow easier movement can help hedgehogs on a local scale. However, since hedgehogs were introduced to the Shetland Islands in 1974, they have become an invasive species, threatening the native seabirds such as terns, dunlins and redshank, all land nesting birds not adapted to defend against land mammals like hedgehogs. Since 2001, large scale efforts aim to relocate hedgehogs onto the mainland to increase the declining populations of seabirds.

Asian elephant

by Aliese

We like to think that we can resist our instincts and act morally. On the other hand, animals are perceived as acting purely on theirs.

In 2019, a herd of elephants in West Bengal shielded a 4-year-old girl with their sturdy legs after her family’s bike crashed into a tree. This shows their remarkable ability for compassion. Do animals have moral values after all?

Let’s have a look at this elephant’s history as an example of human morality! Do you see the hole at the back of its head? This was where it was shot by Sri Lankan authorities in 1881, after they had deemed it a “rogue elephant”.

Do we have the right to claim that we are the ‘paragon of animals’ like Shakespeare once said?

Giant ground sloth

by Abbie

Humans played a significant role in the extinction of the Ice Age megafauna. Around 10,000 years ago, the giant ground sloth was hunted for meat and tool materials by people, which, alongside climate change, contributed to its extinction.

Humans’ interference with the natural world can be both destructive and chaotic, but this is not a tale of power and domination but an example of reliance and desperation, just as many ancient creatures predated upon humans. But the question is, is our meat consumption in modern day a necessity or craving?

Burbot

by Tara

Theories as to whether the burbot is a single species or many led to tissue samples being taken, and as a result many genetic similarities were found between this specimens and Belgian burbots. There are now plans to reintroduce these Belgian burbots into water-systems in Norfolk since our own burbots had been driven to extinction due to habitat destruction and commercial overfishing. This reintroduction of burbots will bring back some balance to our ecosystems and they can coexist well with other organisms.

The question is – will the slaughtering of burbots resume once the populations stabilise? More positively, this story provides hope for other disappearing species, and it also establishes how museum specimens can have a powerful role in conservation projects.

Museum of Zoology: Discovery Space

Migratory birds: the barn swallow

by Aaliyah

Unable to survive in freezing temperatures, this barn swallow is known to travel from places like the UK to places such as sub-Saharan Africa and southern Spain in winter. However, as temperatures rise and winters become warmer, the number of swallows remaining in this country when they would normally be migrating is rising. This is a remarkable indicator of modern and current changes caused by climate change. Also seen is an overall northern shift in the wintering range of migrating barn swallows, again a clear sign of changes but a hopeful indicator that nature is able to adapt to changing temperatures to ensure their survival.

Museum of Archaeology and Antrhopology: Ground Floor

Idealised humanity: our perfect lady

by Elizabeth

When this burial was discovered in 1952, local archaeologists would have seen a female skeleton. The blackened, shining surface of the ‘ribs’ are an artificial attempt to keep bones in place. This value we place in our deceased contrasts starkly with the careless disregard we have for plants. We deforest, tears unshed, but the moment we can give death a face, ‘a granite grin’, then we care, then we cry. In the Roman Arbury skeleton we are reminded of our own mortality. So we dress her up with ribs and poems. But our planet is withering too. Maybe the next time you spot a withering fern, a tear should be shed. A tear for our trodden planet’s changing life. A rebellious tear for change.

For more information and images, see the record in the MAA online catalogue

Palaeolithic hand axe

by Imogen

This palaeolithic hand axe contains a fossilised shell in its centre. It would have been made by hitting the flint with a hammerstone to remove the outer parts of the stone in a process called knapping. The shell seen in the centre would have been there originally, and the axe would have been shaped around it. This shows how this tool was also designed aesthetically and not just practically, revealing that a desire to manipulate nature in a way both functionally and decoratively has existed for thousands of years. As a result, this artefact is a record of how the interaction between humans and nature has existed since the earliest traces of civilisation and is a key aspect of human nature, still very much present today.

For more information and images, see the record in the MAA online catalogue

Museum of Archaeology and Antrhopology: First Floor

Fijian Whale Tooth Necklaces

by Layla

The necklaces seen in the cabinet are made of sperm whale teeth. Before European contact, whales were not hunted in Fiji and instead the ivory would have been collected from beached whales stranded on the shore. These items were regarded as highly valuable and would have originally only been worn by influential individuals such as chiefs because they were so rare. However, the necklaces quickly became more widespread after European contact because of the rise of the whaling industry. In Fijian culture, to this day, there continues to be a huge amount of respect for the teeth of sperm whales which are considered one of the most precious items to give as gifts.

For more information and images, see the record in the MAA online catalogue

Bags from Papua New Guinea

by Scarlett

These spectacular bags are designed by the women of Papua New Guinea and have become a key source of income for the makers.

The straps sit at the very top of the head, descend past the ears and the main bulk of the bag rests on the upper back. Anyone and everyone uses these incredibly versatile bags – women will even carry their young children in them.

Communities of women come together to weave three strings of dried bark or yarn into their traditional, intricate designs, and local flowers are sometimes added to introduce a pop of colour. Businesses have been made from the production and distribution of these bags and they’re available to buy straight from the inspiring women artists.

For more information and images, see the record in the MAA online catalogue

Ghost net turtle

by Rebecca

This ghost net turtle highlights the dangers faced by sea turtles across the world. The sculpture was made by Florence Gutchen who lives in the Torres Strait, the islands between Papua New Guinea and Australia. The only way ghost nets are removed is by human intervention. Showing despite the damage and danger humans have caused, there is hope when we decide to help and reverse the damage done. This object is linked to the green turtle in the Museum of Zoology which is vulnerable due to fishing nets trapping them. These sculptures are symbolic of the help that we can do to protect these animals, it shows a change can be made and there is a positive outcome.

For more information and images, see the record in the MAA online catalogue

Stories of Climate Change for Pacific Islanders

by Dominic

Volcanic islands erupt and sink leaving a coral crown around the remaining raised land. Pacific islanders intertwined with the dense nature of coral atolls learn skills like weaving coconut fibres. These Pacific rings of corals are now at risk due to climate change and rising sea levels that can destroy human homes and ways of life. In the 2000s, the Carteret people of Papua New Guinea were forced to leave their coral islets and resettle on Bougainville Island. Together we can rejuvenate these environments through coral plantation and cultural heritage can be preserved

through communication in the Talanoa dialogue set up by the United Nations. Reducing polluting emissions and responsibly recycling helps combat climate change from your own home.

Kiribati Puffer Fish Helmet

by Madeleine

A remarkable display of local use of resources, the Kiribati helmet is a key element of the community’s culture and connection to nature. Under British colonisation this was lost. Now, after gaining independence in 1979, the people of Kiribati are reclaiming their culture, visiting museums like MAA in an attempt to relearn the craft. The contemporary helmet on display is not the same species used by ancestors, an unfortunate consequence of being forced to lose touch with heritage

and tradition. Thus the dual nature of humankind’s need to take what is not ours is highlighted, but also the eventual triumph in the relationship between humans and the natural world. Revival has been given to a once dying artform.

For more information and images, see the record in the MAA online catalogue

Hook figure of initiated man from the Sepik River

by Imogen

The use of the crocodile in both men’s initiation ceremonies and the creation myth of the Sepik demonstrates the importance of the animalistic in defining the human. Humans often find ourselves caught between an animalistic, primal world, and an idealistic, abstract one. Yet, the emergence of both heaven (the abstract) and earth (the physical) from the crocodile complicates such a view. It is plain that, in speaking with minds alien to our own, animals provide blank canvases for the abstract concepts we long to see and touch.

For more information and images, see the record in the MAA online catalogue

Museum of Archaeology and Antrhopology: Second Floor

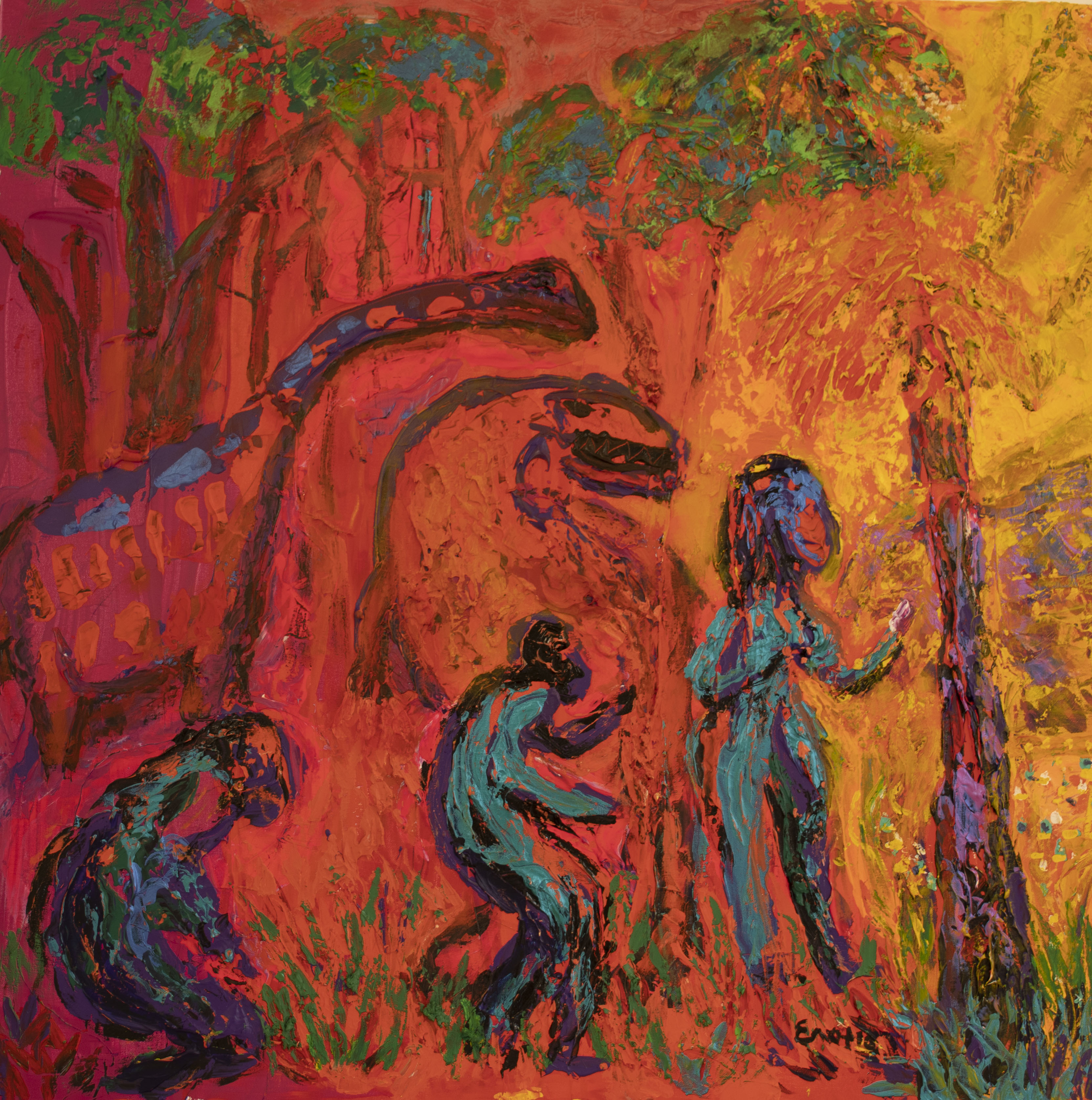

From Eden to Ecocide: A Tale of Human Impact

by Esha

This painting by Nigerian artist Enotie Ogbebor depicts the story of humanity’s impact on the natural world. It demands attention to be drawn to the devastation bleeding into the earth at our hands, punctuating the differences between life on Earth with us and life on Earth without. The vibrancy and warmth of the first picture in this triptych pours out the happiness, beauty and harmony of animals with nature, which is clearly and gradually forced out by humans as we become increasingly comfortable with our presence here. It looks in the pictures as if we used to be afraid of the expansive grandeur of the earth and rightly so – but over time we’ve sucked the colour and life out, creating an imbalance as darker colours dominate.

For more information and images, see the MAA website

Star Carr

by Chloe

Lake Flixton formed as a result of the natural cycles of climate change at the end of the last Ice Age. Here, we observe a glimpse of the settlement that formed as a result of this glacial meltinduced lake, Star Carr. The lake provided the habitat for animals and plants, supplying food and physical resources. It is as if the climate held the power, in creating the conditions that allowed an entire settlement to form and thrive.

In contrast, climate change today is the human-accelerated threat that envelops much of our modern lives, causing sea levels to rise or changes to weather patterns. From our place of power, we have inflicted great damage on things around us. We are responsible for the issue, and should therefore be able to solve it.

For more information and images, see the record in the MAA online catalogue

Four Sons of Horus Amulets

by Carmen

We have always had a strong connection with the natural world. This is clear in the Four Sons of Horus Amulets, which the Egyptians chose to protect them, even in death. Animals were very important to them, and their deities would hold particular characteristics of certain animals. For example, Duamtuet, one of the four Sons of Horus, has a jackal head. Jackals are part of the dog family and they hold characteristics of a protector, companion, and guide, which is why he is chosen to look after one of the organs – the stomach. It is interesting to think that there are

attributes that are found in humans, deities and animals. Do you think that you have

any traits that certain animals also hold?

For more information, see the record in the MAA online catalogue

The Shabti

by Ben

The Ancient Egyptian ‘shabti’ was made from natural materials, such as wood or limestone. In its use as an aid for those with wealth or power to be treated kindly by Thoth and Osiris, gods of death and the underworld, respectively, the shabti shows a desire to exploit nature throughout humanity. Creation of shabtis later shifted to faience, perhaps displaying a greater care for the human aesthetic use of the natural world, or perhaps a showcase of the roots of stewardship in an environment and society one wouldn’t expect. This is a clear indicator for us as a human race that

we cared about Earth millennia ago, raising the question of: why can’t we care now?

For more information and images, see the record in the MAA online catalogue

Egyptian Pottery

by Lydia

Item 9 is a piece of Egyptian pottery from the predynastic period estimated from 4500 – 3100 BCE. The red pottery paints ibexes, antelopes and flamingos using clay and Nile silt. Nature is used to shape the pottery as the animals serve as symbols of the landscape placing them in Egyptian artistic and cultural value. Connection to the Nile allowed Egyptian civilisation to grow, being used for transport, water and fertile soil for food. Utilising nature has allowed the expanding of civilisations into the present placing our relationship as co-dependent for the benefit of humanity. Drawing onto the initial naturalistic inspiration of the pottery, hope can be formed through the historical connection to Earth’s ecosystem.

For more information and images, see the record in the MAA online catalogue