Alec Christie, PhD student in the Conservation Evidence group of the Department of Zoology writes:

Go to your doctor and they’ll give you the best treatment based on the scientific evidence. So why can’t we do the same for biodiversity? Recently we’ve seen a flurry of important work highlighting the continuing decline of biodiversity, including David Attenborough’s documentary Extinction: the facts. It’s also very encouraging to hear from a recent study, with input from many conservation organisations in the David Attenborough Building that sits above the Museum, that conservation efforts have prevented the decline of 28-48 bird and mammal species. Conservation is working, but do we know more specifically what is working and why?

Using evidence can help us learn from others’ past failures and successes, and help find the best ways to conserve species threatened with extinction. As an example of why it’s really important to use scientific evidence, bat gantries/bridges have cost millions of pounds to install across busy roads in the UK, and yet they have been shown to be ineffective at preventing bats getting hit by cars. Using evidence to make decisions really is a no-brainer because it can make conservation more efficient and effective. If conservationists only rely on their past experiences or expert opinion to inform their decision making, they may miss out on a lot of useful information that can save them precious time and resources.

The Conservation Evidence project based in the David Attenborough Building, has been leading the way in collating the scientific evidence that has tested which conservation actions work (e.g. does using different types of nets help reduce accidental deaths of seabirds?). The database contains 6616 studies that have quantitatively tested 2399 conservation actions (at the time of writing) across fields ranging from amphibian, bird, and mammal conservation, to forest, farmland, and peatland conservation and it’s growing all the time.

Three recent studies have taken advantage of this massive scientific evidence base to identify what knowledge gaps exist in our understanding of what works in conservation, and what this means for making evidence-based decisions for amphibian, bird, and primate conservation.

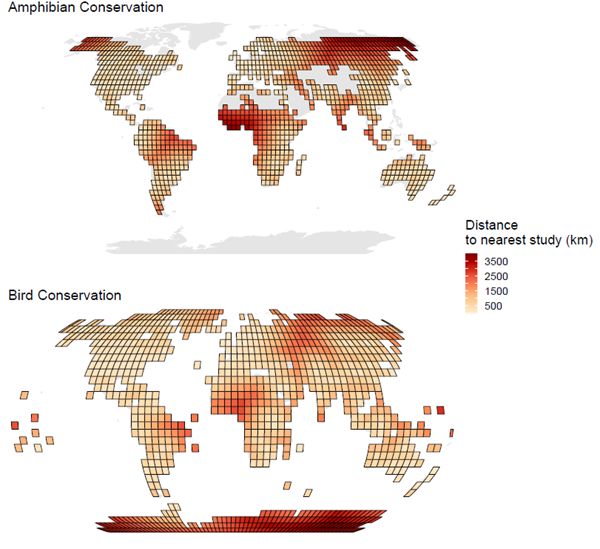

In the first study, we found that scientific evidence was extremely patchy for both amphibians and birds. Most concerningly of all, fewer studies were conducted in locations with greater numbers of threatened species (e.g. in the tropics). This strange pattern is driven by the fact that very few studies were conducted outside of North America, Europe and Australasia, which collectively make up 90% of amphibian studies and 84% of bird studies. Staggeringly, 64% of amphibian studies and 63% of bird studies were conducted in the UK, USA, or Australia alone. Studies outside of these regions also tended to be poorly-designed, which means very often we’re making critical decisions in places where conservation is greatly needed with potentially unreliable evidence.

There were also large biases in the animal groups that were studied, for example, there was little or no evidence for entire taxonomic orders of amphibians (e.g., limbless caecilians) and birds (e.g., hornbills and hoopoes). Many more were also badly underrepresented relative to the percentage of threatened species they contain. This is the opposite to what we would want to see, as groups with more threatened species should receive more research attention. It’s the same as if you were a doctor in A&E, you’d surely want to prioritise patients with the most life-threatening injuries, wouldn’t you?

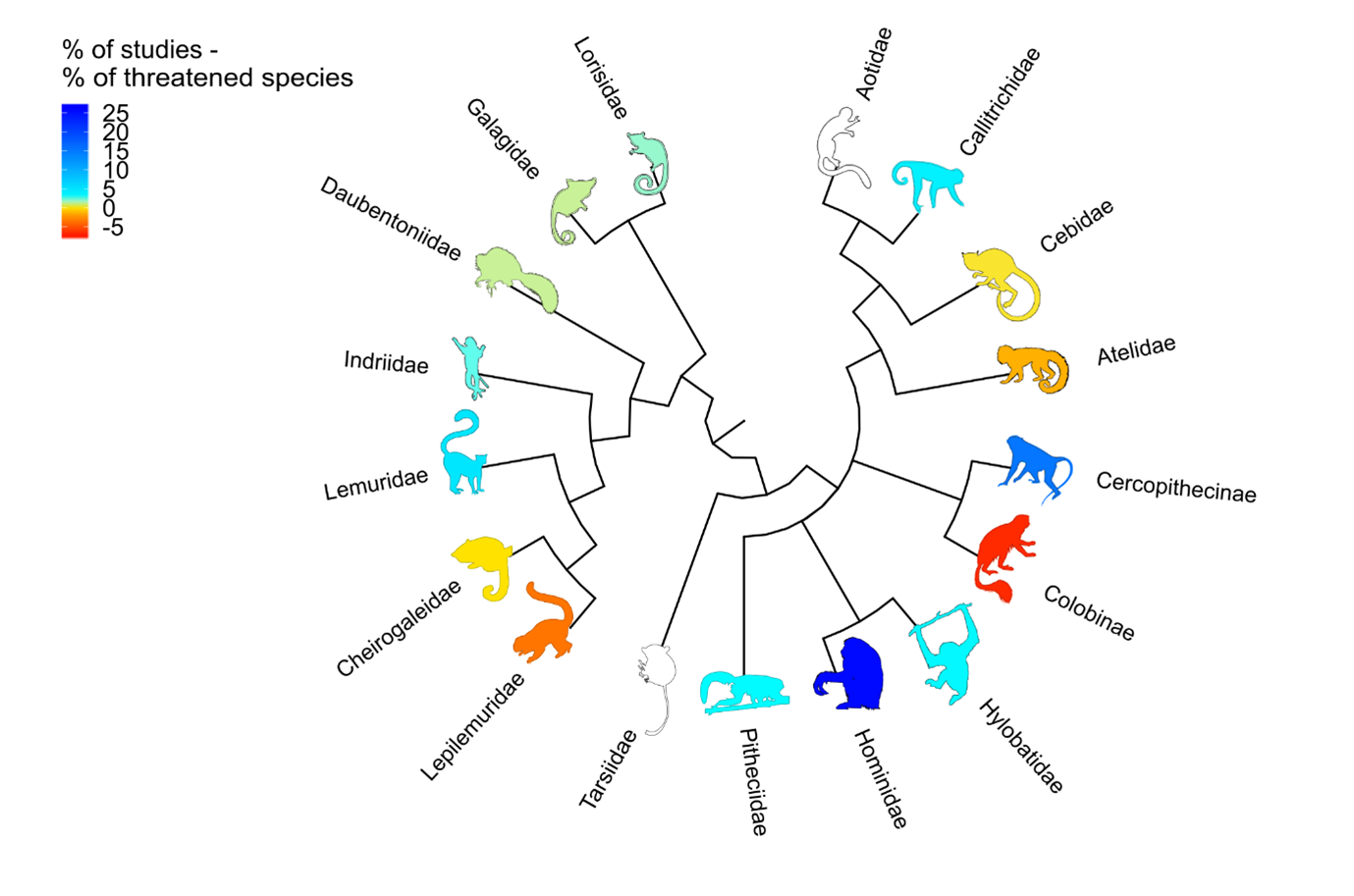

In the second study, we found similarly severe gaps and biases in the evidence for primates. Only 14% of the 500 primate species were studied and just 12% of threatened species – of which most are great apes or larger monkey species. Even whole families, such as tarsiers in south-east Asia, or the night monkeys of Central and South America were absent from the evidence base.

In the third study, we shifted the focus to answer the question: ‘For the average conservationist, how much relevant scientific evidence is there for them to make decisions?’. This is important because to make decisions, conservationists typically prefer to use evidence that is locally relevant to them (i.e. studies that are conducted on very similar species or habitat). As an analogy, if you’re deciding which restaurant is best to eat at in Cambridge, you don’t want to look at reviews of restaurants in Oxford because they’re not relevant. We found that conservationists in locations where most threatened species live (e.g., the tropics) will find it particularly difficult to find studies on relevant species or habitats. There was far less relevant evidence for species and habitats that were more threatened with extinction than there were for the most commonly studied species and habitats.

These biases and gaps in the scientific evidence base highlight a major mismatch between where we test conservation actions and where we need to implement them. It also highlights how little research has been done in many regions and for many threatened species on the best ways to save them from extinction. Back to our A&E example, the problem we essentially have is that we know how to treat the least life-threatening injuries well, but very little idea of how to treat patients who are dying in front of us. Doctors wouldn’t stand for that, so why should conservationists?

To improve the evidence base, we need funding organisations to dedicate and prioritise more funding to test conservation actions for threatened species and in underrepresented parts of the world (e.g., large parts of Africa, South America, Russia, and Asia). We need both scientists and conservationists to collaborate more to design reliable studies to test these actions, overcome barriers to publishing their findings, and collate this evidence so that others can benefit from this knowledge (as the Conservation Evidence project is doing). I hope that our studies will help demonstrate the importance of filling these knowledge gaps, help us build a better understanding of what works in conservation, and ultimately help protect even more species from extinction. With hard work, I am confident we’ll soon be prescribing treatments to save species just like doctors do.